venturesomeoverland

Venturesome Overland

COOPER DISCOVERER - "At Least We're Not on Everest": Once Around the White Rim

“At least we're not on Everest!”

That little phrase had become something of a mantra for us on this trip to Utah's canyon country.

It was our refrain when confronted with some minor inconvenience: a slow leak in the air mattress, battling fatigue during the 11 hour drive from Montana, forgetting the box of wine at home, or a fast exhaust leak on the Jeep.

We were inspired by Anatoli Boukreev's harrowing account of the infamous climbing disaster on Mount Everest in 1996, The Climb: Tragic Ambitions on Everest. Audiobooks are our favorite method for whiling away the long hours on the road, and Boukreev's intense counterpoint to Jon Krakauer's more widely read Into Thin Air was just the ticket for this adventure.

It is inevitable that things will go wrong. The unexpected shunts your plans, lets you know you are not in as much control as you thought you were. But really, how bad can it get? We're not freezing to death in some rock fissure below the Hillary Step, right?

Right?

The Shafer Trail – only one way down. It plummets 1500 vertical feet in only 2 miles from the Island in the Sky Mesa (White Rim Road, Canyonlands National Park).

Canyonlands National Park's White Rim Road is one of the most iconic off-road travel experiences in North America. Built by uranium speculators in the 1950s, the 100-mile White Rim Road is now one of the only ways to reach some of the more remote parts of Canyonlands Island in the Sky District. It's not particularly technical, and it is well-trod by backcountry enthusiasts of all stripes, from Jeep pilots, to mountain bikers, to hikers.

This is for good reason. The scenery, the jump-off points for exploration, the vast expanse of wilderness, and careful management by the National Park Service mean that you can dial in your own expedition without feeling crowded. It's easy to feel like you are discovering all of it for the first time.

But, like Everest – the highest, easiest mountain with the most people on it – the White Rim Road can lull you into a sense of effortless adventure. The sun is shining, the way is dry and welcoming, and you're two-thirds of the way to the top.

The White Rim Road.

In mid-November the trip started uncertainly (even before it began) with a check engine light in the Jeep late on the day before we were supposed to leave. A minor exhaust leak in the manifold had become a major one, and an oxygen sensor had failed. $60 and a cold hour on my back in the Montana darkness solved the sensor problem, but even after a liberal application of JB Weld, the leak persisted.

Itching to get on the road early the next day, I glumly resigned myself to tolerate the fractured exhaust. I was frustrated because I like our vehicle to be fully prepared and in top shape before big trips. The leak nagged at my subconscious and disrupted my sleep – it seemed to portend only more problems.

After a restless night, our friend and frequent partner in adventure, Zach joined me and Julie the next morning. With the comfort of coffee and bagels, the three of us steeled our resolve and our backsides for the loud 750 mile drive ahead of us.

As we droned south on Interstate 15, the booming and popping of the exhaust faded gradually into background noise, and my dark mental cloud dissipated as the snow-capped ranges of southwest Montana unfolded before us: the Flint Creeks, Anacondas, Pioneers, Beaverheads, and Tobacco Roots.

On the stereo, Anatoli Boukreev recounted the myriad dangers of the high Himalayas – frostbite, pulmonary edema, collapsing seracs in the Khumbu ice fall. Falling.

Hey, this Jeep may be loud, and we've got a long way to go, but at least we're not on Everest.

At lunch time, tacos served fresh from an old school bus in Dillon, Montana energized us for the road ahead.

Taco bus! Dillon, Montana

We feel guilty about Utah sometimes.

Living in Montana, we are surrounded by over 27 million acres of public lands, more than enough to explore for a lifetime. And yet, we find ourselves drawn to the desert Southwest at least twice every year. Why do we subject ourselves to the highway haul and the extra expenses of time, money, and effort? Just for a change of scenery?

It goes deeper than that – the desert inspires us in ways that mountains and forests do not. We are desert seekers, and even the long journey itself is part of the process. If deserts were easy, would they hold the same appeal?

A slanted land – Canyonlands and The La Sal Mountains.

After pizza in Price, Utah, we roared in late at Green River State Park. I winced as we idled noisily past our neighbors in the campground at 11:00pm, searching for our site. But sleep came easily after the marathon day at the wheel.

We were greeted the next morning by the volunteer camp host, an affable retiree from Mississippi in a straw hat and a polo shirt. He and his wife traveled the country in their RV volunteering in state and National parks. The Oregon coast was their next stop, but we were packing in too much of a hurry to linger over conversation. The canyons called.

Watchfulness – Green River State Park, Utah

After a grocery and gas stop in Moab, we doubled back north to route 313, the Island in the Sky Mesa, and the White Rim Road. A quick check-in at the ranger station yielded a fair weather report (20% chance of scattered rain), and a thumbs-up on the road conditions.

We had secured our travel permit online for the White Rim a few weeks earlier. This is an important step – the Park Service manages the traffic on the Road to minimize impacts and ensure a bit of solitude for everyone. I signed in blue ink on the “Trip Leader Agreement” line, Permit No. 2015-8842.

Did that make me the “trip leader”? I suppose it did. As I aired down the tires, the big blue cube of late autumn Utah sky welcomed us to the depths of the canyons.

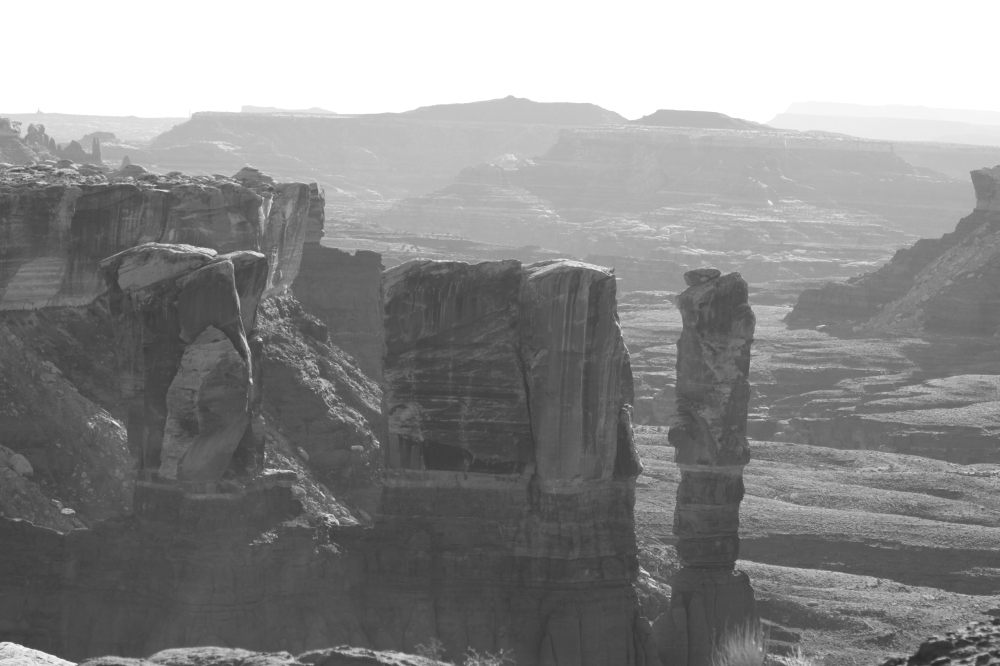

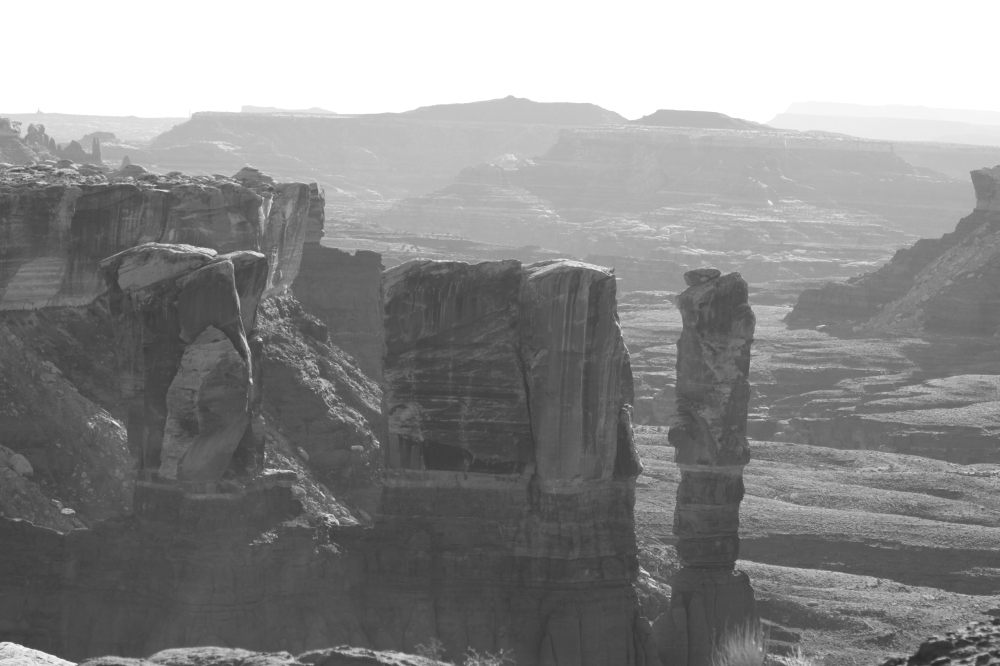

The Wingate and White Rim sandstones, which are relatively hard, are underlaid by the softer Chinle and Moenkopi formations, which erode much faster. Hence these fantastic balancing acts.

Gettin' dusty.

Airport Campsite C.

Home away from home at Airport camp.

The brave steed, Airport Tower.

Near Musselman Arch.

Island in the Sky Mesa.

The first two days of our four day trip on the White Rim went mostly as planned – we had the thousands of acres to ourselves, taking hikes to explore the rock formations and side canyons, soaking in the sunshine and silence, and enjoying leisurely stops for photographs, snacks, and just plain old gawking at the scenery. Conversation fell away, and we switched off Anatoli's harrowing Himalayan narrative. We entered that state of easy communion with the landscape and the light that only the desert offers.

There were problems – there always are. Our air mattress developed a slow leak, necessitating midnight refills; we discovered that we forgot the box of wine on the counter at home; and the MacGyver fix I attempted on the exhaust at Airport camp failed after half an hour. Minor inconveniences. At least we weren't on Everest.

Something new to see around every corner. White Rim Road.

Balancing acts.

Eyes on the road, please. It's hard to get lost on the White Rim, but easy to find the unexpected.

Candlestick Tower, Candlestick camp.

Breakfast – the most important meal of the day. Candlestick camp.

Candlestick camp is one of the most spectacular places you can rest your head in North America. Perched on the rim of a plunging undercut canyon of the Green River, it takes in 360 degree views of the northern district of The Maze, the Buttes of the Cross, the Candlestick Tower, the rugged ridge of the Walker Cut pass, and over the hill to the south and east, the Turk's Head. It feels like the end of the earth, and that feels good.

Sunrise from Candlestick Campsite.

____________________________

Check out more of our adventures at http://mtdrift.com

“At least we're not on Everest!”

That little phrase had become something of a mantra for us on this trip to Utah's canyon country.

It was our refrain when confronted with some minor inconvenience: a slow leak in the air mattress, battling fatigue during the 11 hour drive from Montana, forgetting the box of wine at home, or a fast exhaust leak on the Jeep.

We were inspired by Anatoli Boukreev's harrowing account of the infamous climbing disaster on Mount Everest in 1996, The Climb: Tragic Ambitions on Everest. Audiobooks are our favorite method for whiling away the long hours on the road, and Boukreev's intense counterpoint to Jon Krakauer's more widely read Into Thin Air was just the ticket for this adventure.

It is inevitable that things will go wrong. The unexpected shunts your plans, lets you know you are not in as much control as you thought you were. But really, how bad can it get? We're not freezing to death in some rock fissure below the Hillary Step, right?

Right?

The Shafer Trail – only one way down. It plummets 1500 vertical feet in only 2 miles from the Island in the Sky Mesa (White Rim Road, Canyonlands National Park).

Canyonlands National Park's White Rim Road is one of the most iconic off-road travel experiences in North America. Built by uranium speculators in the 1950s, the 100-mile White Rim Road is now one of the only ways to reach some of the more remote parts of Canyonlands Island in the Sky District. It's not particularly technical, and it is well-trod by backcountry enthusiasts of all stripes, from Jeep pilots, to mountain bikers, to hikers.

This is for good reason. The scenery, the jump-off points for exploration, the vast expanse of wilderness, and careful management by the National Park Service mean that you can dial in your own expedition without feeling crowded. It's easy to feel like you are discovering all of it for the first time.

But, like Everest – the highest, easiest mountain with the most people on it – the White Rim Road can lull you into a sense of effortless adventure. The sun is shining, the way is dry and welcoming, and you're two-thirds of the way to the top.

The White Rim Road.

In mid-November the trip started uncertainly (even before it began) with a check engine light in the Jeep late on the day before we were supposed to leave. A minor exhaust leak in the manifold had become a major one, and an oxygen sensor had failed. $60 and a cold hour on my back in the Montana darkness solved the sensor problem, but even after a liberal application of JB Weld, the leak persisted.

Itching to get on the road early the next day, I glumly resigned myself to tolerate the fractured exhaust. I was frustrated because I like our vehicle to be fully prepared and in top shape before big trips. The leak nagged at my subconscious and disrupted my sleep – it seemed to portend only more problems.

After a restless night, our friend and frequent partner in adventure, Zach joined me and Julie the next morning. With the comfort of coffee and bagels, the three of us steeled our resolve and our backsides for the loud 750 mile drive ahead of us.

As we droned south on Interstate 15, the booming and popping of the exhaust faded gradually into background noise, and my dark mental cloud dissipated as the snow-capped ranges of southwest Montana unfolded before us: the Flint Creeks, Anacondas, Pioneers, Beaverheads, and Tobacco Roots.

On the stereo, Anatoli Boukreev recounted the myriad dangers of the high Himalayas – frostbite, pulmonary edema, collapsing seracs in the Khumbu ice fall. Falling.

Hey, this Jeep may be loud, and we've got a long way to go, but at least we're not on Everest.

At lunch time, tacos served fresh from an old school bus in Dillon, Montana energized us for the road ahead.

Taco bus! Dillon, Montana

We feel guilty about Utah sometimes.

Living in Montana, we are surrounded by over 27 million acres of public lands, more than enough to explore for a lifetime. And yet, we find ourselves drawn to the desert Southwest at least twice every year. Why do we subject ourselves to the highway haul and the extra expenses of time, money, and effort? Just for a change of scenery?

It goes deeper than that – the desert inspires us in ways that mountains and forests do not. We are desert seekers, and even the long journey itself is part of the process. If deserts were easy, would they hold the same appeal?

A slanted land – Canyonlands and The La Sal Mountains.

After pizza in Price, Utah, we roared in late at Green River State Park. I winced as we idled noisily past our neighbors in the campground at 11:00pm, searching for our site. But sleep came easily after the marathon day at the wheel.

We were greeted the next morning by the volunteer camp host, an affable retiree from Mississippi in a straw hat and a polo shirt. He and his wife traveled the country in their RV volunteering in state and National parks. The Oregon coast was their next stop, but we were packing in too much of a hurry to linger over conversation. The canyons called.

Watchfulness – Green River State Park, Utah

After a grocery and gas stop in Moab, we doubled back north to route 313, the Island in the Sky Mesa, and the White Rim Road. A quick check-in at the ranger station yielded a fair weather report (20% chance of scattered rain), and a thumbs-up on the road conditions.

We had secured our travel permit online for the White Rim a few weeks earlier. This is an important step – the Park Service manages the traffic on the Road to minimize impacts and ensure a bit of solitude for everyone. I signed in blue ink on the “Trip Leader Agreement” line, Permit No. 2015-8842.

Did that make me the “trip leader”? I suppose it did. As I aired down the tires, the big blue cube of late autumn Utah sky welcomed us to the depths of the canyons.

The Wingate and White Rim sandstones, which are relatively hard, are underlaid by the softer Chinle and Moenkopi formations, which erode much faster. Hence these fantastic balancing acts.

Gettin' dusty.

Airport Campsite C.

Home away from home at Airport camp.

The brave steed, Airport Tower.

Near Musselman Arch.

Island in the Sky Mesa.

The first two days of our four day trip on the White Rim went mostly as planned – we had the thousands of acres to ourselves, taking hikes to explore the rock formations and side canyons, soaking in the sunshine and silence, and enjoying leisurely stops for photographs, snacks, and just plain old gawking at the scenery. Conversation fell away, and we switched off Anatoli's harrowing Himalayan narrative. We entered that state of easy communion with the landscape and the light that only the desert offers.

There were problems – there always are. Our air mattress developed a slow leak, necessitating midnight refills; we discovered that we forgot the box of wine on the counter at home; and the MacGyver fix I attempted on the exhaust at Airport camp failed after half an hour. Minor inconveniences. At least we weren't on Everest.

Something new to see around every corner. White Rim Road.

Balancing acts.

Eyes on the road, please. It's hard to get lost on the White Rim, but easy to find the unexpected.

Candlestick Tower, Candlestick camp.

Breakfast – the most important meal of the day. Candlestick camp.

Candlestick camp is one of the most spectacular places you can rest your head in North America. Perched on the rim of a plunging undercut canyon of the Green River, it takes in 360 degree views of the northern district of The Maze, the Buttes of the Cross, the Candlestick Tower, the rugged ridge of the Walker Cut pass, and over the hill to the south and east, the Turk's Head. It feels like the end of the earth, and that feels good.

Sunrise from Candlestick Campsite.

____________________________

Check out more of our adventures at http://mtdrift.com

Last edited: