maxingout

Adventurer

Expeditionary Navigation In The Arabian Desert

Not all expeditionary navigational problems are created equal, and your approach to navigation varies with terrain, capability of the vehicle, and degree of access to the land. Limited access makes navigation more challenging, and unlimited access gives you hundreds of options when you plan your expedition.

Most regions of the developed world place major restrictions on what you can do, where you can go, and the amount of permission required to undertake your trip.

The Saudi Arabian desert is different. You have unrestricted access to the desert once you are outside major metropolitan areas. When you are fifty kilometers outside of Riyadh, you can travel off road for 500 to 1500 kilometers in any direction. You enter the desert wherever you please, and you exit the desert at will. Furthermore, the Arabian desert does not contain land mines, and there are no civil wars to complicate off road adventures.

Principles of desert navigation vary according to where you make your overland trip. Many locations require you to travel on well-defined tracks, and figuring out your location is as simple as reading your odometer to see how far you have progressed down a particular track.

Large areas of the Arabian Desert have no tracks. You simply head cross country with the only limits being imposed by geographic obstacles such as escarpments and mountain ranges. To a large extent, the amount of fuel you carry and the time available determine what you can accomplish on your expedition.

in highly developed countries, navigation involves keeping track of your position as you drive on known routes with lots of landmarks. In the Arabian desert, navigation is more like navigating at sea. Wide open spaces and few landmarks guide you as you explore a sea of sand.

SITUATIONAL AWARENESS

Situational awareness forms the foundation of successful expeditionary travel. Situational awareness means that you know yourself, your vehicles, and the desert in which you travel. You must know your vehicle well and understand its capabilities and limitations.

Each year that I lived in Arabia, I read stories in the newspaper about people who died in the desert because they were not situationally aware.

Joshua Slocum, (the first man to sail single-handed around the world) said, "You must know the sea, and know that you know it, and know that it was meant to be sailed upon."

A similar statement could be made about desert expeditions. "You must know the desert, and know that you know it, and know it was meant to be driven upon."

When you head into the desert, you have to understand what you are doing. The desert is unforgiving to the unprepared, and a demolition derby awaits those who know not what they do.

If you have a well-prepared vehicle with plenty of fuel and spare parts, and if you understand the terrain and navigational problems associated with your expedition, you will have an awesome adventure.

ROUTE FINDING AND NAVIGATION

The minute you leave the asphalt and enter the desert, you instantly discover the difference between route finding and navigation. I never understood this difference until I went on an expedition into the Arabian sands.

Route finding is different than navigation.

Navigation is about where you are and the general direction you need to travel to reach your destination. Navigation involves the big picture of your trip from start to finish.

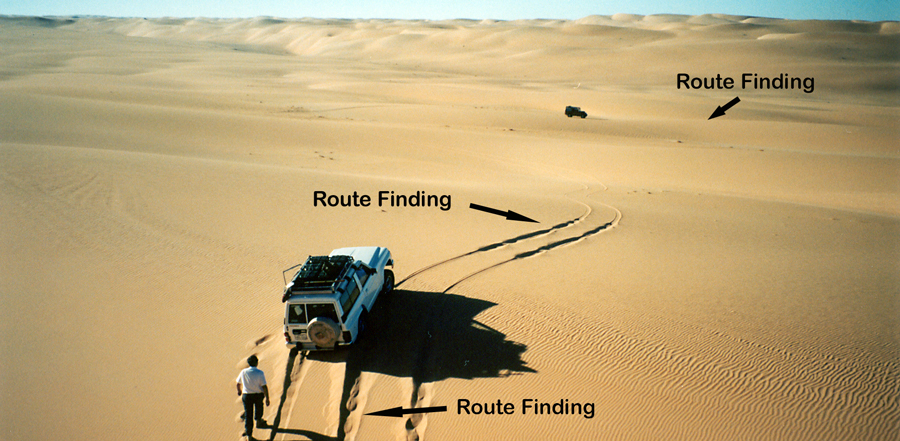

Route finding focuses on what is happening in the next 100 to 300 feet in front of the vehicle. Driving in the dunes and soft sand is a two person job. The route finder sits up front with the driver and tells him what is ahead. The driver concentrates on driving safely through the next fifty feet. The route finder tells the drover to turn to the right, to the left, to continue straight, or to stop because of conditions directly ahead.

Although it's possible for a solo operator to do both the driving and route finding, it can be exhausting and difficult work in challenging conditions. When driving in soft sand with lots of hummocks and in short closely spaced dunes, you have to zig zag a great deal. It's much easier to have one person doing the route finding through the sea of sand, so the driver can concentrate on getting the vehicle successfully through the next fifty feet of wily desert terrain.

Navigation is about the big picture, and route finding is navigation on a micro scale.

Even when you travel on a Bedouin track, it helps to have a route finder spot rocks and cross tracks that can destroy a vehicle's steering and suspension.

Two Bedouin tracks crossing at ninety degrees to each other can cause a lot of damage to your vehicle. The cross track sometimes is elevated like speed bumps or depressed like ditches, and if you hit them at speed, you can bend steering components and traumatize your suspension. Unsecured gear in your truck may go airborne. I know of vehicles that have had unsecured flying gear come forward and crack their windshield.

The route finder warns about hazards on the track so you have time to safely react. The driver looks at challenges immediately in front of the vehicle, and the route finder warns about dangers 200 to 300 feet ahead. A good route finder makes the driver look like a professional, and a poor route finder makes a driver look like an idiot who always gets stuck and frequently damages his vehicle.

Route finding is micro navigation. The route finder records GPS waypoints, courses, distances, geographical features, Bedouin camps, and any other data that could be helpful if a problem occurs. We always record the location of Bedouin tents in remote areas of the desert, because if things go badly, Bedouins would be a big asset in a true emergency.

We once came upon a serious accident in the desert where young expatriates had rolled their vehicle. Saudis graciously loaded the most seriously injured individual into their Land Cruiser and took the victim to the hospital because the ambulance refused to go into the desert to render assistance.

Route Finding

Route finding informs the driver of what he or she should do next. Route finding usually deals with what is in front of the vehicle, but occasionally it focuses on what is behind.

In this picture, the Nissan Patrol did not make it out of the sand hole, and the driver got out of the car and walked back in the track to test the sand behind the vehicle. The Nissan could go directly backward, or could back up to the right or left. The driver tested the sand by walking on it in different areas behind the vehicle. Once he discovered an area of firm sand, he backed his vehicle onto that patch and used it as his launching pad to escape his sandy prison. In this case, he discovered firm sand directly behind the vehicle, and the Nissan backed straight up. Next, he put the accelerator all the way to the floor and said good-bye to the sand trap.

In front of the vehicle, route finding reveals a short patch of soft sand on level ground. With enough speed it should be fairly easy to get through that patch without bogging down as long as he transits the area with gusto. Beyond the soft patch, the sand is firm all the way out to the Defender parked in the distance waiting for the Nissan to catch up.

It's not by chance that the Defender is parked on a gentle down slope. Fully loaded expeditionary vehicles always park on a down slope so they won't dig in and get stuck when they start to move once again. Parking on an upslope is a big no no, and is the sign of a novice in the desert sands.

Navigation

Navigation is the big picture of your expedition. It shows what you plan to do, and reveals the contingencies available if things don't work out. It allows you to define your navigational problem in concrete terms. You plot distances and directions on the map, and calculate fuel requirements for all contingencies.

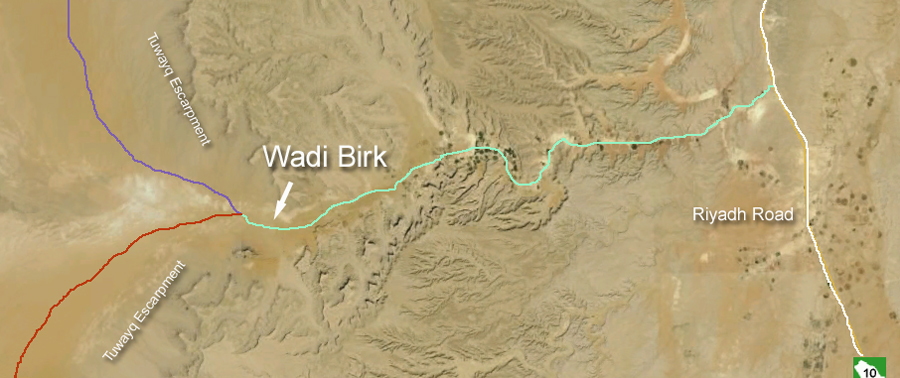

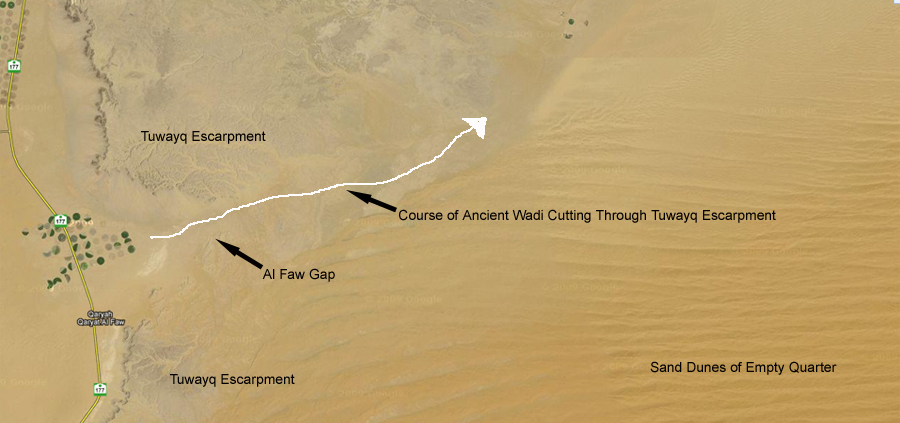

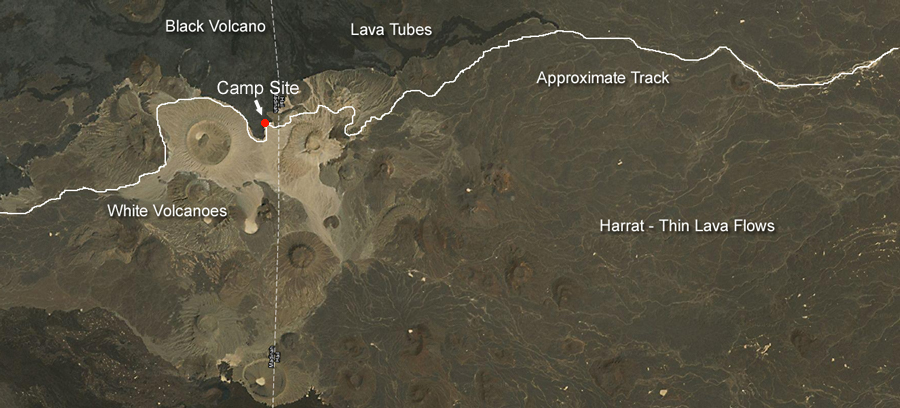

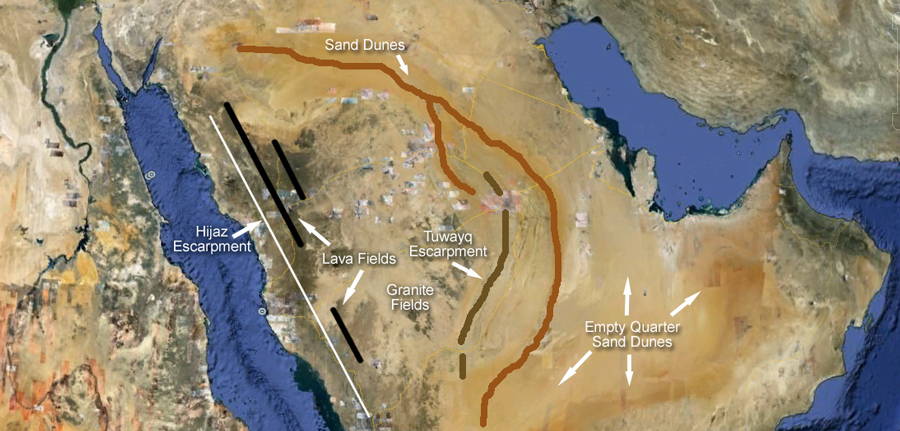

The map of the southern Nejd Quadrangle of Saudi Arabia contains a smorgasbord of expeditionary adventures. I have driven thousands of kilometers in this quadrangle. Each line represents a different trip that starts in Riyadh. The white lines are highways that define the entry and exit points into the desert. The thousand foot high Tuwayq escarpment runs north to south for more than 900 kilometers on the right side of the map. The granite fields are in the center of the map. The lava fields (harrat) are on the left side of the map.

Lava, granite, and escarpment define what is impossible, and white roads and colored desert tracks scratch the surface of what is possible to accomplish in this quadrangle.

The red track cuts through the Tuwayq escarpment at Wadi Birk and heads south west on sheet sand and low dunes curving over to the tombs of Bir Zeen. The purple track takes you to the granite mountains of Ibn Huwayil and Jebel Sabah. The light blue track takes you from Khamsin to the tombs of Bir Zeen, and then through the lower, middle, and upper granite fields with optional stops at Ibn Huwayil and Jebel Sabah. The dark blue track explores the upper and middle granite fields before heading north to the Mecca Road. The green track comes south from Riyadh west of the Tuwayq escarpment on gravel plain and sheet sand.

To reach the light blue track from Riyadh, you either travel 200 kilometers west on Mecca Road (Highway 40) before turning into the desert, or travel 600 kilometers south from Riyadh and pass through the town of Khamsin before entering the desert and heading north toward Bir Zeen on the light blue track.

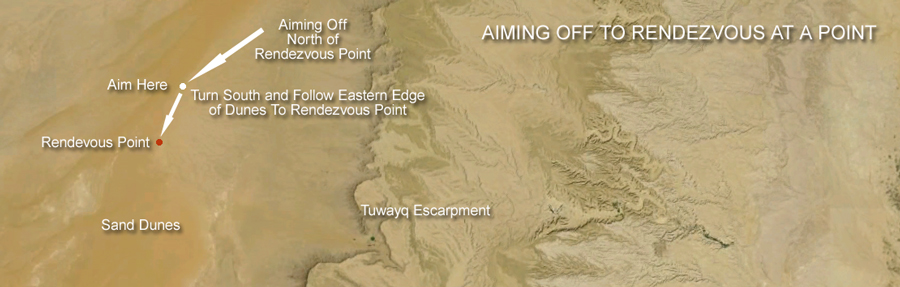

When you navigate in the southern Nejd quadrangle, the first thing you need to do is define the entry and exit points for your trip. The Tuwayq escarpment limits your options on the east side of the quadrangle. You can pass through the escarpment in at least three places where large wadis cut through the Tuwayq. Another option is to do an end run around the escarpment at Khamsin by traveling south for 600 kilometers on paved highway. If you want to do most of the trip off road, you can follow desert tracks south for 500 kilometers after you leave Riyadh. These locations make good entry points, but they are not as good for exit points because the Tuwayq escarpment limits your exit options.

When you construct a navigational plan, it's a good idea to have flexibility to allow for contingencies at the end of the trip. You don't want to make getting out of the desert into a navigational ordeal where you must hit a specific point or your exit strategy fails. If the only point of exit is where Wadi Birk cuts through the escarpment, you need to plan your exit well. If your exit point is Mecca Road, you have hundreds of kilometers of asphalt available to complete your exit strategy. Simply head north until you hit Mecca Road and turn right toward Riyadh.

A well constructed navigational plan means that navigation is easy and worry free. A poorly constructed navigational plan adds unnecessary stress and places your expedition at risk.

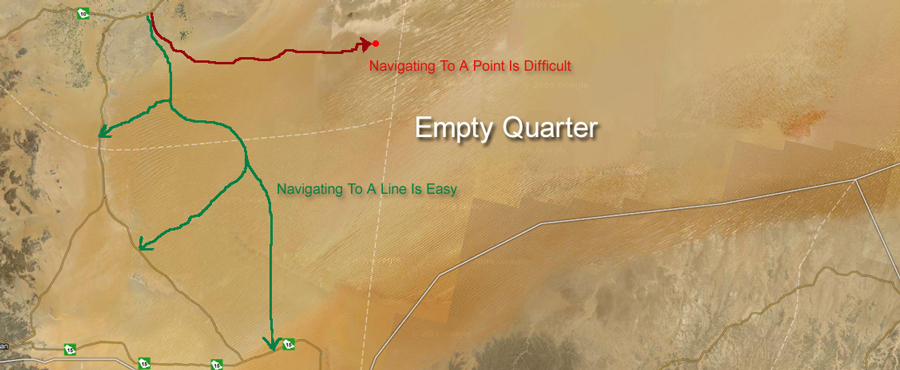

THE NAVIGATIONAL BOX

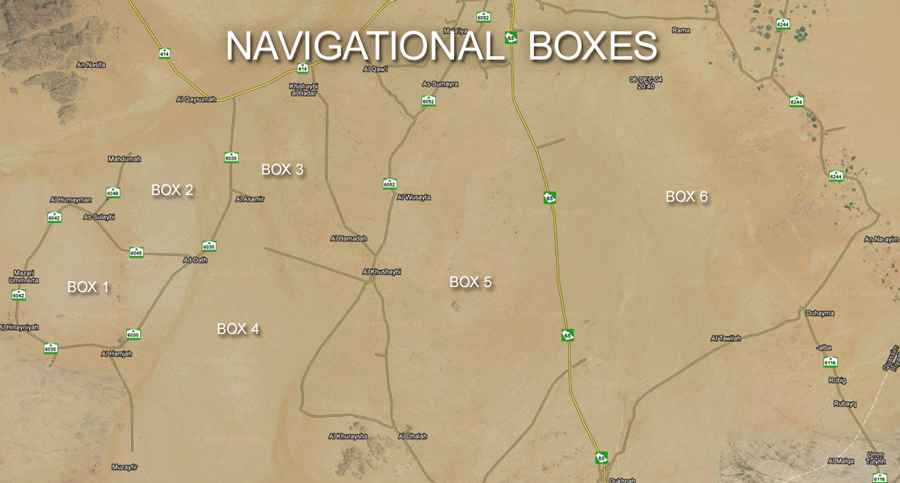

When we head out on a 200 to 400 km trip into the desert, we construct a navigational box that encloses the area of exploration. The edges of the navigational box are lines to which we travel in order to escape the navigational box.

To facilitate our exploration, we often enter a navigational box on the largest Bedouin track we can find. That large track transports us quickly to the area that we want to explore. Usually desert tracks become progressively smaller as we head deeper into the desert. Eventually the track might disappear entirely, and at that point, we drive cross country as we explore the countryside.

As long as there is a track, route finding is easy and travel is not difficult. Once we run out of tracks, things might get challenging as the loss of the track often means there is geographical barrier that limits how far we can travel in a particular direction.

An escarpment or severely dissected terrain may render travel impractical and not worth the effort because it puts the vehicles and expedition at unnecessary risk. Breaking vehicles in deep desert is serious business. Nothing stops expeditionary travel quite as effectively as broken down vehicles.

When it's time to leave our navigational box, we simply select a small Bedouin track that heads in a favorable direction. The small track eventually leads to a larger one. Eventually we discover a major track that takes us to one of the edges of our navigational box. Frequently the edge of the box is an asphalt road, and once we hit the asphalt, we say good-bye to the desert and drive the rest of the way home on the highway.

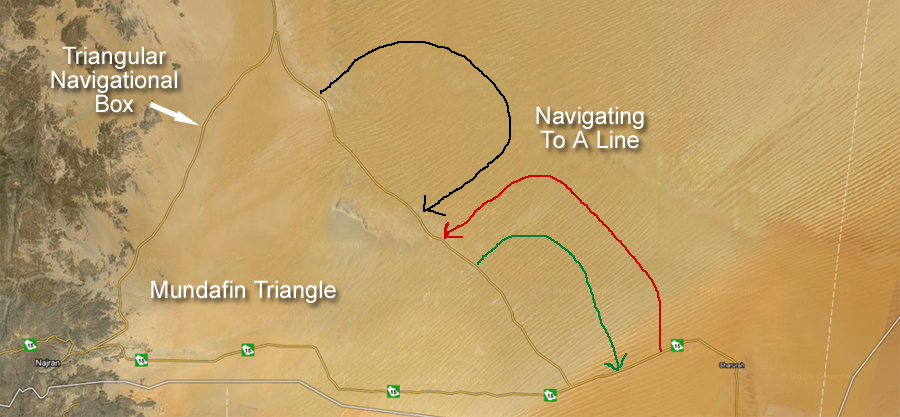

The navigational box doesn't need to be a rectangle. Any size or shape of box works fine. You may travel in a navigational triangle. It doesn't matter how many sides the navigational box has. What is important is that it has sides that you can aim for in order to get out of the desert and back to civilization.

In the satellite photo, navigational boxes 1, 5, and 6 are completely enclosed, and if you simply drive in a straight line, you will eventually escape from the box. Boxes 2, 3, and 4 have at least one open side, and your navigational plan should take you to one of the enclosed sides.

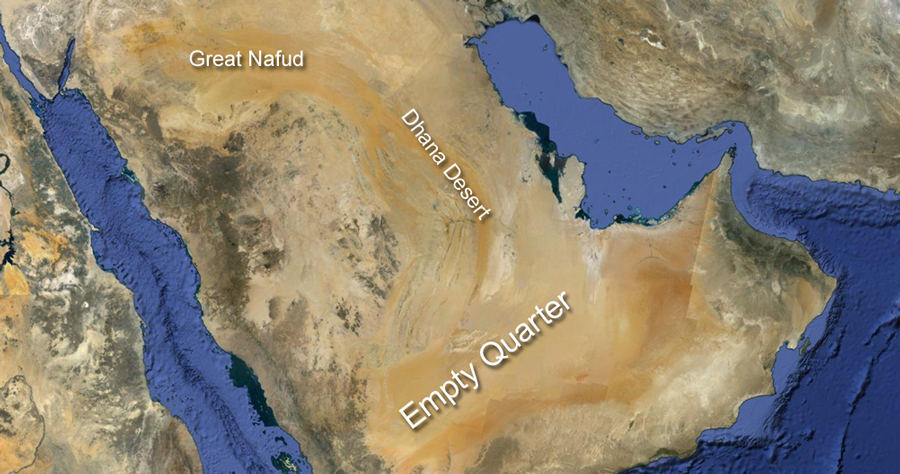

ARABIAN SHIELD

Maps often don't do a good job of representing the lay of the land.

The map of Saudi Arabia looks flat, but nothing could be further from the truth.

The Arabian shield is elevated more than 10,000 feet in the west, tilting all of Arabia on it's side as it gradually slopes down to sea level in the Persian Gulf. The 10,000 foot tilt creates the massive Hijaz escarpment in western Arabia, and the tilt creates escarpments and wadis all across the country.

Tectonic plates in the Red Sea form a spreading center that continually adds land mass to the Arabian Peninsula on the eastern side of the Red Sea and to Egypt and Sudan on the western side of the Red Sea. As new land forms, it elevates the western edge of the Arabian Shield creating a massive 10,000 foot escarpment. As it pushes the land upward, it tilts the entire Arabian shield. When you are on the top of the Hijaz escarpment, it is effectively downhill all the way to the Persian Gulf.

The unique geology of Arabia offers dozens of geographical regions accessible for exploration. The tilted Arabia Shield creates wadis that run west to east until they encounter mountains and obstacles that divert their easterly flow.

Escarpments, lava fields, and ribbons of sand tend to be oriented along a north/south axis. Wadis on top of the shield flow west to east until diverted by geographical barriers.

Each section of Arabia presents unique navigational challenges that reflect differences in regional geology. It's the geology that makes expeditions on the Arabian peninsula so interesting. It's unrestricted access that makes exploration so much fun.

So how do you navigate in a place like Saudi Arabia? Is it hard or easy?

Last edited: