Get your tickets to THE BIG THING 2026!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

One-Way Ticket: Colorado to South Sudan

- Thread starter Containerized

- Start date

NetDep

Adventurer

Amazing trip report and look forward to more -- although not planning a travel to Africa (although a dream it would be) I learn tons reading your awesome report and seeing your pictures - thank you for sharing that with all of us...

"6) My girlfriend, who is the one with the medical background, has totally rethought our first aid and trauma kit through this process. It began with a small backpack with the basics, a suture kit, etc. Now it's a whole 1520 Pelican case."

My other question - where you received the training was already dealt with. My question here was, with some medical background, can you list the contents - or hit the high points - on what/how to pack and what you might have learned about medical/trauma issues on your trip -- thanks in advance!!

"6) My girlfriend, who is the one with the medical background, has totally rethought our first aid and trauma kit through this process. It began with a small backpack with the basics, a suture kit, etc. Now it's a whole 1520 Pelican case."

My other question - where you received the training was already dealt with. My question here was, with some medical background, can you list the contents - or hit the high points - on what/how to pack and what you might have learned about medical/trauma issues on your trip -- thanks in advance!!

Containerized

Adventurer

NetDep - The biggest challenge, and I've spent hours with my girlfriend planning what to do in medical emergencies (as we're often 5+ hours from a properly-equipped hospital), is the balance between urgency and equipment size/weight. Yes, you can build an EMT-style "what's up" bag, but that's just too much crap to carry with you. People say, "Well, also, be careful to never travel alone." Frankly, this might work for aid workers who are in the region for a week or two, but it's total bull$*)# advice to give people who are in country for 15, 18, or 30 months. Often, when I'm on fieldwork, I'm alone (and often she travels alone). That's just the reality of it. And often I go somewhere and have to park the vehicle and walk, hike, or ride (usually on the back of a dirtbike) from the RV point to the meeting itself. So what to do?

Our solution is to have two sizes of first aid kits and to communicate where the vehicle is to at least one other person whenever we leave it. The small first aid kit is kept in the passenger door panel of the FJC. It includes light wound dressings for two small sites, two epipens, a modern (velcro-and-plastic-pencil style) tourniquet, paper/pencil, ten tabs of Vicodin, two small vials of stopbleed pellets, a small section of space blanket (because the stopbleed stuff gets crazy hot when used), etc. - and a map of hospitals and airstrips. It is a soft-sided rectangluar bag with a handle (an old London St. John's Ambulance bag, to be specific) and has lots of pouches. We've completely repacked it. It goes everywhere - if you leave the vehicle, it goes in your pack. When you pack your pack in the morning, you leave enough room for the small vehicle medkit.

I'd recommend printing (on A4 paper) maps of hospitals and airstrips in the area you're driving to, if it's a destination drive rather than part of a larger expedition - I have added several sites (including clearing sites usable for rotary aircraft) in northern Uganda to my Garmin map, and I'm happy to share this process (though it's navigation and I guess off-topic here?).

The larger kit (1520 Pelican) is marked with a large white cross on a black case so it's obvious to other people if we need to be treated by someone else with access to the vehicle. The load area of the FJC is always loaded so this is the last thing in and it is always loaded with the cross facing rearward. The case itself is packed with a HIV-endemic area in mind, with gloves on top as a reminder to anyone who opens the case. It includes pressure dressings, rigid (packed) gauze to pack wounds or stabilize impaled objects, and the other "heavy duty" stuff you should have on hand, but aren't going to carry on the hike from the vehicle to the site. It's prioritized around things we can resupply - for instance, we began with airtight dressing tape (basically a plastic sterile very wide tape) but plastic wrap also works as a replacement. Carrying flat scalpel kits (gamma/ozone treated sterile, blister packaged) rather than opening your suture kit every time you need a scalpel is smart. Carrying good tweezers (Rubis in Switzerland makes amazing products) rather than crappy ones, given that this is something you are likely to use, is a good idea. Carrying enough sterilizing agent (alcohol or alternatives) rather than tearing open swab or pad packages is smart. Injectables are an area of controversy, but we carry the Vietnam-era "vial box" rather than the modern kits, just because they are more resistant to damage (albeit heavier) - local anesthetic being probably the most versatile and useful injectable you could carry, if you only carried one.

I would say medical bag weight/space versus probability of use is one of the toughest calculations to make when designing a vehicle, and I really appreciate how much thought my girlfriend has put into this area, and how much work we've done together on figuring out various scenarios. Talk with your co-driver, navigator, partner, etc. Discuss what you'd do in certain situations and what kinds of risks are acceptable to you. Have a policy in place for others (when you encounter others who would benefit from your help or supplies) and stick to it when you encounter people who are injured (you will) no matter how tempting it is to intervene or how pathetic the person's (or the person's children's) requests for aid may be. Remember, Objective 1 is to get from Point A to Point B, not to hand out painkillers on the roadside.

If something is unlikely to be used, don't dismiss it. For example, a round Heimlich valve (flutter valve) is basically a flat sticker when in its package, weighs nearly nothing, and could save your life for valuable time in event of pneumothorax. So, in my opinion, it goes in the bag. Maybe someone misses you with a knife when a bar fight breaks out, maybe a large fuel or natural gas tank explodes near you (this has happened to us), or something else happens that generates matter with enough mass and energy to puncture a lung if you're unlucky. Don't put anything in the bag that you wouldn't feel comfortable using - that discomfort will be MAGNIFIED by a situation in the field.

Finally, be realistic and consider that you may be the casualty. Do not carry unmarked drugs (for borders and checkpoints, if for no other reason) and think in terms of someone local, with little education, treating you. Make it obvious what things are if someone else needs to use the bag. If necessary, draw a picture on a piece of white duct tape. Mark anything containing sharps with a picture of a needle. Include a card printed with the emergency numbers for the embassies of the countries to which you hold citizenship - better, include a direct consular number that you know a person will answer 24 hours per day, rather than something that gets forwarded to London (or Washington or wherever). Put a spare key to your vehicle in the first aid kit on a bright red keychain, so someone who dumps it out will be able to find the key and drive you somewhere if you're unconscious (we have a cheap keychain photo frame, like people use for pictures of their dogs/kids, on this key with a picture of the truck so they know which vehicle is ours). Though some dealers don't know how to do the programming, even the newest Toyota vehicles can have four duplicate keys plus the original key (we have five keys for our 2012 Tacoma).

Our solution is to have two sizes of first aid kits and to communicate where the vehicle is to at least one other person whenever we leave it. The small first aid kit is kept in the passenger door panel of the FJC. It includes light wound dressings for two small sites, two epipens, a modern (velcro-and-plastic-pencil style) tourniquet, paper/pencil, ten tabs of Vicodin, two small vials of stopbleed pellets, a small section of space blanket (because the stopbleed stuff gets crazy hot when used), etc. - and a map of hospitals and airstrips. It is a soft-sided rectangluar bag with a handle (an old London St. John's Ambulance bag, to be specific) and has lots of pouches. We've completely repacked it. It goes everywhere - if you leave the vehicle, it goes in your pack. When you pack your pack in the morning, you leave enough room for the small vehicle medkit.

I'd recommend printing (on A4 paper) maps of hospitals and airstrips in the area you're driving to, if it's a destination drive rather than part of a larger expedition - I have added several sites (including clearing sites usable for rotary aircraft) in northern Uganda to my Garmin map, and I'm happy to share this process (though it's navigation and I guess off-topic here?).

The larger kit (1520 Pelican) is marked with a large white cross on a black case so it's obvious to other people if we need to be treated by someone else with access to the vehicle. The load area of the FJC is always loaded so this is the last thing in and it is always loaded with the cross facing rearward. The case itself is packed with a HIV-endemic area in mind, with gloves on top as a reminder to anyone who opens the case. It includes pressure dressings, rigid (packed) gauze to pack wounds or stabilize impaled objects, and the other "heavy duty" stuff you should have on hand, but aren't going to carry on the hike from the vehicle to the site. It's prioritized around things we can resupply - for instance, we began with airtight dressing tape (basically a plastic sterile very wide tape) but plastic wrap also works as a replacement. Carrying flat scalpel kits (gamma/ozone treated sterile, blister packaged) rather than opening your suture kit every time you need a scalpel is smart. Carrying good tweezers (Rubis in Switzerland makes amazing products) rather than crappy ones, given that this is something you are likely to use, is a good idea. Carrying enough sterilizing agent (alcohol or alternatives) rather than tearing open swab or pad packages is smart. Injectables are an area of controversy, but we carry the Vietnam-era "vial box" rather than the modern kits, just because they are more resistant to damage (albeit heavier) - local anesthetic being probably the most versatile and useful injectable you could carry, if you only carried one.

I would say medical bag weight/space versus probability of use is one of the toughest calculations to make when designing a vehicle, and I really appreciate how much thought my girlfriend has put into this area, and how much work we've done together on figuring out various scenarios. Talk with your co-driver, navigator, partner, etc. Discuss what you'd do in certain situations and what kinds of risks are acceptable to you. Have a policy in place for others (when you encounter others who would benefit from your help or supplies) and stick to it when you encounter people who are injured (you will) no matter how tempting it is to intervene or how pathetic the person's (or the person's children's) requests for aid may be. Remember, Objective 1 is to get from Point A to Point B, not to hand out painkillers on the roadside.

If something is unlikely to be used, don't dismiss it. For example, a round Heimlich valve (flutter valve) is basically a flat sticker when in its package, weighs nearly nothing, and could save your life for valuable time in event of pneumothorax. So, in my opinion, it goes in the bag. Maybe someone misses you with a knife when a bar fight breaks out, maybe a large fuel or natural gas tank explodes near you (this has happened to us), or something else happens that generates matter with enough mass and energy to puncture a lung if you're unlucky. Don't put anything in the bag that you wouldn't feel comfortable using - that discomfort will be MAGNIFIED by a situation in the field.

Finally, be realistic and consider that you may be the casualty. Do not carry unmarked drugs (for borders and checkpoints, if for no other reason) and think in terms of someone local, with little education, treating you. Make it obvious what things are if someone else needs to use the bag. If necessary, draw a picture on a piece of white duct tape. Mark anything containing sharps with a picture of a needle. Include a card printed with the emergency numbers for the embassies of the countries to which you hold citizenship - better, include a direct consular number that you know a person will answer 24 hours per day, rather than something that gets forwarded to London (or Washington or wherever). Put a spare key to your vehicle in the first aid kit on a bright red keychain, so someone who dumps it out will be able to find the key and drive you somewhere if you're unconscious (we have a cheap keychain photo frame, like people use for pictures of their dogs/kids, on this key with a picture of the truck so they know which vehicle is ours). Though some dealers don't know how to do the programming, even the newest Toyota vehicles can have four duplicate keys plus the original key (we have five keys for our 2012 Tacoma).

Last edited:

Containerized

Adventurer

People have said they wanted to see more of coastal East Africa (TZ, Kenya, Ethiopia, Somaliland), so here are a few more:

Somebody's gotta make sure the Coca-Cola gets there in Nairobi.

Fixing any confusion about encased meats near Nairobi:

Me, discovering a random fountain in pretty much the middle of nowhere in Kenya.

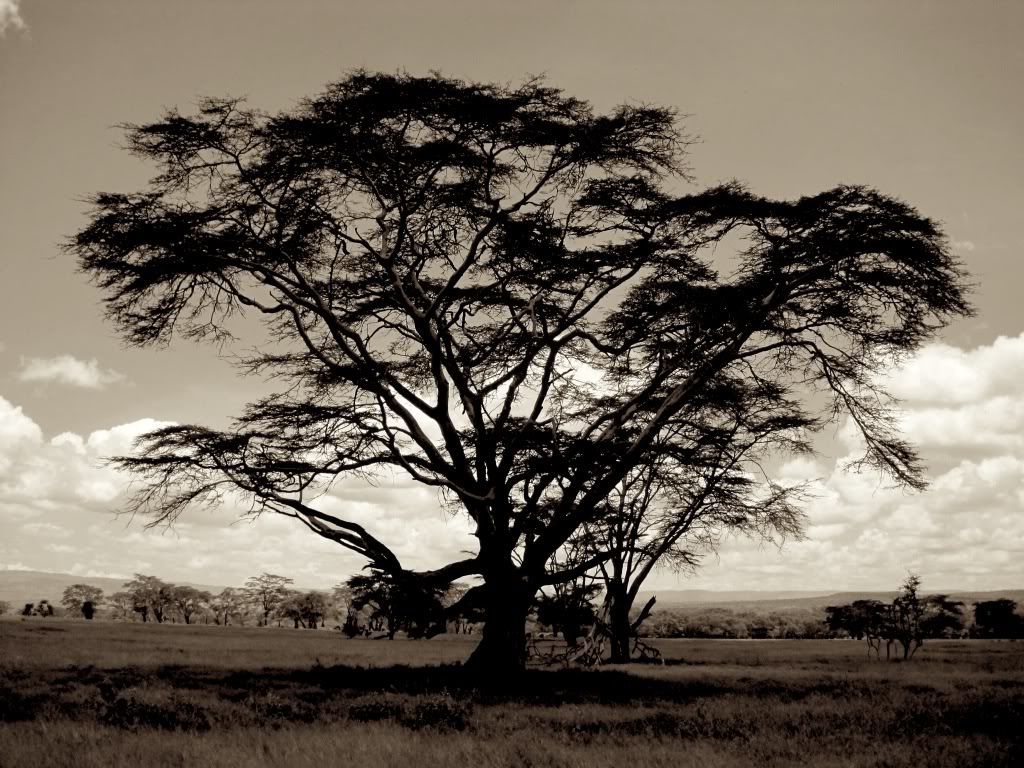

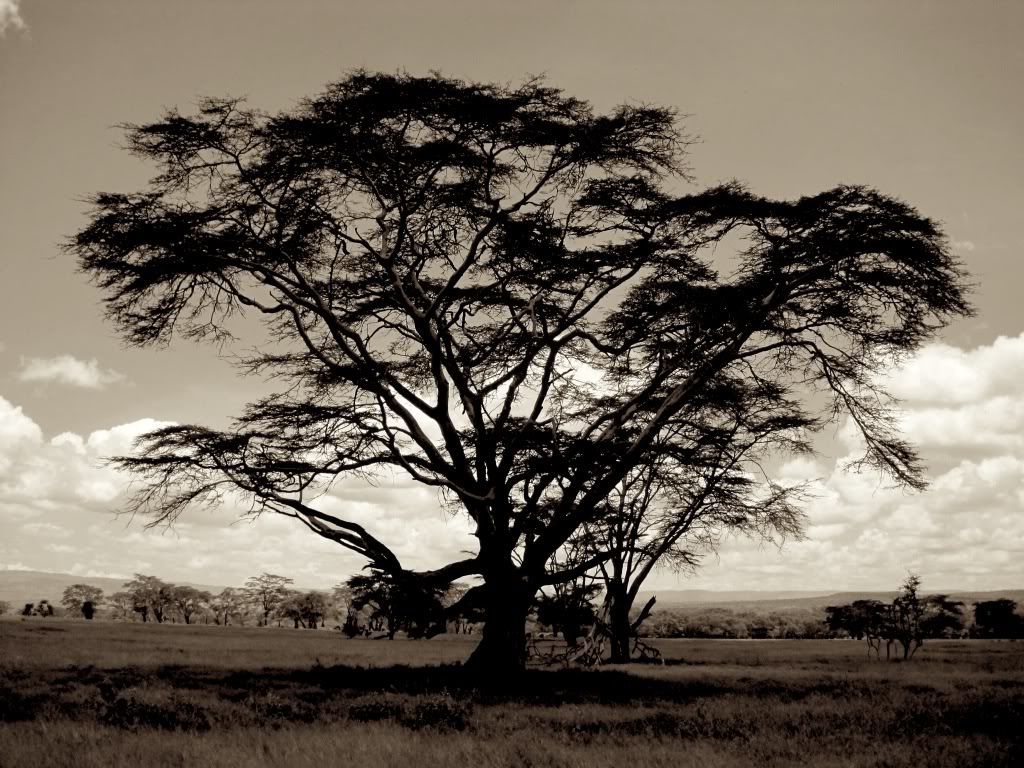

A gorgeous old tree near the Kenya-Somali border:

A well-deserved break by the pool after a week on the road:

And climbing:

The drive from Kenya to Ethiopia during the dry season is characterized by these roads:

Me, posing with the KWS bus - one of many spotted in our journeys:

Flamingoes, anyone?

Approaching the most efficient ferry crossing in Kenya:

Imagine being thirsty for eighty days. That's how these guys feel when the dry season ends:

Somebody's gotta make sure the Coca-Cola gets there in Nairobi.

Fixing any confusion about encased meats near Nairobi:

Me, discovering a random fountain in pretty much the middle of nowhere in Kenya.

A gorgeous old tree near the Kenya-Somali border:

A well-deserved break by the pool after a week on the road:

And climbing:

The drive from Kenya to Ethiopia during the dry season is characterized by these roads:

Me, posing with the KWS bus - one of many spotted in our journeys:

Flamingoes, anyone?

Approaching the most efficient ferry crossing in Kenya:

Imagine being thirsty for eighty days. That's how these guys feel when the dry season ends:

Containerized

Adventurer

Creativity and art are not scarce in Africa:

Exchanging stories and cookies with fellow travelers.

The fertile foothills that eventually lead to Ethiopia's interior deserts:

The mysterious mountains of Kenya:

Needless to say, the path down is not a straight road...

A less-is-more vehicle in Nairobi:

For the 70-series fanboys... this is the best ambulance I've seen in East Africa. Most look like they've been through three wars.

Four guys in a D110 would be enough to make me think twice about causing trouble:

If you can't find a Shell or a Total, find one of these:

Exchanging stories and cookies with fellow travelers.

The fertile foothills that eventually lead to Ethiopia's interior deserts:

The mysterious mountains of Kenya:

Needless to say, the path down is not a straight road...

A less-is-more vehicle in Nairobi:

For the 70-series fanboys... this is the best ambulance I've seen in East Africa. Most look like they've been through three wars.

Four guys in a D110 would be enough to make me think twice about causing trouble:

If you can't find a Shell or a Total, find one of these:

taco2go

Explorer

Thank you for sharing!

^^ cool name, Joash

Containerized- thanks for sharing such detailed and informative reports. Good tips for long term stay in any developing country/continent i would say.

And such an interesting professional perspective- your unique observations and commentary definitely add to the photos. Look forward to more and safe travels.

Containerized

Adventurer

Joash - Good question. Honestly, it's the ability to modify. If I build trucks and bring them where I go, I know the shop (the shop I use has modified 10+ vehicles for me over the last 15 years), I know the parts, I know everything has been done perfectly, I know everything is better than the day it left the factory. Meanwhile, in northern Uganda where I live, the best carpenter in town doesn't even have a drill (he has a nail he drives in and pries out every time he needs to make a hole). The facilities just don't exist to do serious work on these vehicles or to make them into what I need. Sure, if I wanted a stock Landcruiser 70 TX station wagon, I could have bought one (going price in Uganda is about $130,000), but modifying an FJ and shipping it is far cheaper and much closer to what I wanted.

Containerized

Adventurer

Don't mind at all. Biggest cost, by far, is taxes to get your Ugandan license plate. These are, of course, negotiable... but even with local people doing the negotiating who do this for a living, you're going to get screwed a bit. Rough costs were $4k for the shipping (Baltimore to Dar es Salaam), $12k for taxes and "fees" (interpret that as you will) to get the vehicle insured, into the various countries involved, get plates, get vehicle carnets, etc. Note that $12k is for more than a year of overland travel. If I had wanted tax-free plates, I could have avoided most of the Ugandan cost (about $10k of the $12k), but then you have to export the vehicle when you're finished with it. As I wanted to re-sell the vehicle when I left this consulting project, I needed to pay the import tax (the subsequent buyer will not owe tax). Now, you have to put up a bond to take a private vehicle into conflict regions in South Sudan and Sudan, but this was not the case in the past.

I used Maria at ATL Global for the major legs of vehicle shipping in this itinerary and she has been a fantastic resource, very good to work with, and knowledgeable about ro-ro options in the region, also. I would highly recommend her. I don't know her personally and have never worked for ATL Global - just making a recommendation as a happy customer. We've worked with other people, including FedEx's cargo folks and regional freight forwarders, and have not received the same level of attention to detail or customer service.

As others have said on this forum for a long time, having lots of copies of all paperwork is helpful. Having both high and low appraisals of your vehicle on-hand from a friendly Toyota dealer is also helpful when negotiating tariffs and so on. I had an appraisal with me that my FJ was worth about $15k, which of course the authorities didn't believe, but it helped set the tone for the bargaining over taxes. In the local market, a 2007 FJ with 50,000 miles might bring as much as $60,000, so the range for bargaining is enormous.

I bought the vehicle from a dealer in Wisconsin for $19k and probably have $15k in parts and labor in it at this point, plus $1500 of spare parts brought to Uganda for maintenance.

I used Maria at ATL Global for the major legs of vehicle shipping in this itinerary and she has been a fantastic resource, very good to work with, and knowledgeable about ro-ro options in the region, also. I would highly recommend her. I don't know her personally and have never worked for ATL Global - just making a recommendation as a happy customer. We've worked with other people, including FedEx's cargo folks and regional freight forwarders, and have not received the same level of attention to detail or customer service.

As others have said on this forum for a long time, having lots of copies of all paperwork is helpful. Having both high and low appraisals of your vehicle on-hand from a friendly Toyota dealer is also helpful when negotiating tariffs and so on. I had an appraisal with me that my FJ was worth about $15k, which of course the authorities didn't believe, but it helped set the tone for the bargaining over taxes. In the local market, a 2007 FJ with 50,000 miles might bring as much as $60,000, so the range for bargaining is enormous.

I bought the vehicle from a dealer in Wisconsin for $19k and probably have $15k in parts and labor in it at this point, plus $1500 of spare parts brought to Uganda for maintenance.

Last edited:

Similar threads

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 1K

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 1K