You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

TerraLiner:12 m Globally Mobile Beach House/Class-A Crossover w 6x6 Hybrid Drivetrain

- Thread starter biotect

- Start date

biotect

Designer

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

Attachments

-

unnamed-11.jpg574 KB · Views: 9

unnamed-11.jpg574 KB · Views: 9 -

unnamed-13.jpg528.4 KB · Views: 10

unnamed-13.jpg528.4 KB · Views: 10 -

Untitled-1.jpg579 KB · Views: 10

Untitled-1.jpg579 KB · Views: 10 -

Joaquin-Sorolla-spanish-impressionist (22).jpg640.6 KB · Views: 12

Joaquin-Sorolla-spanish-impressionist (22).jpg640.6 KB · Views: 12 -

Fumee-dambergris-sargent-detail.jpg552.8 KB · Views: 11

Fumee-dambergris-sargent-detail.jpg552.8 KB · Views: 11 -

unnamed-16.jpg512.6 KB · Views: 11

unnamed-16.jpg512.6 KB · Views: 11 -

The_Daughters_of_Edward_Darley_Boit,_John_Singer_Sargent,_1882_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg523.4 KB · Views: 12

The_Daughters_of_Edward_Darley_Boit,_John_Singer_Sargent,_1882_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg523.4 KB · Views: 12 -

John_Singer_Sargent_-_Carnation,_Lily,_Lily,_Rose_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg528.7 KB · Views: 13

John_Singer_Sargent_-_Carnation,_Lily,_Lily,_Rose_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg528.7 KB · Views: 13 -

Edinburgh_NGS_Singer_Sargent_Lady_Agnew.jpg525.9 KB · Views: 12

Edinburgh_NGS_Singer_Sargent_Lady_Agnew.jpg525.9 KB · Views: 12 -

Bougereau.jpg549.3 KB · Views: 12

Bougereau.jpg549.3 KB · Views: 12

Last edited:

biotect

Designer

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

4. The stupidity of remaining merely traditional......

********************************************

However, with that said, simultaneously I think it's just willfully ignorant to paint in 2016 as if one were living in 1816. It's both aesthetically and politically reactionary to paint as if the visual and conceptual innovations of the 20th century never happened. In 2003 a review appeared in the New York Times of student work produced at the Florence Academy of Art, and described such work as "… inertly composed still lifes, laughable allegories and preciously romantic self-portraits ... glazed by decades of exposure to tobacco smoke." See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Academy_of_Art , http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/12/a...sm-revisited-the-florence-academy-of-art.html , http://www.florenceacademyofart.com , and http://www.florenceacademyofart.com/en/student-gallery/ . I've taken a few summer courses at the Florence Academy, and this is an accurate description.

Although I do admire the skill of "New Classical" painters associated with the ARC, the Florence Academy, and the New York Academy, perhaps because I am also a trained philosopher, their work almost always leaves me unsatisfied in terms of content. Mere demonstration of artisanal skill is not enough, but unfortunately most of those engaged in “New Classicism” seem to demonstrate little else. Referring back to the ARC website, take a look through some of the portfolios of the best currently practicing “Living Masters” painters – see http://www.artrenewal.org/pages/livingartists.php . Although artisanal skill has returned – and then some – spiritually or intellectually satisfying content is mostly missing. Most of their paintings are single-figure compositions, or even worse, mere portraits, and it’s always hard to suggest an interesting narrative with just one figure.

What's most obviously missing in such paintings is a “will to expression”: a will to depict humans for some specific reason, because the artist wants to say something about the kinds of creatures that we humans are. Pre-19th century figurative Art always expressed values that were much larger than the Art World itself, so there is a certain irony in how New Classical painters make mere demonstration of traditional painterly skill "the main event". As per modern Abstract-expressionist painters, the "how", the mark-making, the painterly precision and/or bravura, becomes an end in itself. Content becomes irrelevant, and all that matters is Art for Art's sake. Although New Classicists like to imagine themselves reviving pre-modern figuration, given their focus on form instead of substance, and given the absence of truly interesting content in most of their work, their sensibility seems modernist to the core. They are reviving merely the husk, the shell of the pre-modern figurative tradition; they are reviving mere style and technique. Their paintings then become little more than fetish-objects demonstrating consummate life-drawing and life-painting skill; they become mere egocentric, self-referential manifestations of painterly prowess. But such paintings don't actually say anything, they don't "speak" to viewers in a meaningful or significant way.

To put the point most forcefully: if these artists really did want to say something, they would show more willingness to take up the challenge of multi-figure, narrative composition. Because whenever one puts two or more figures into a painting, even if one did not intend a narrative meaning, viewers will try to find one. If such "academic" or "New Classical" artists were truly interested in communicating with viewers and expressing something, they would recognize that the most important traditional figurative painting has always been multi-figure historical or religious allegory. Mere single-figure portraits never had much status, because they lacked the kind of intellectual and spiritual content that can only be communicated through the use of multiple figures.

********************************************

5. And yet the danger of becoming merely a creature of one's time......

********************************************

Now there is a huge difference between the output of such "academic" or "New Classical" artists featured on Art Renewal's website, versus the work of contemporary figurative artists like Jenny Saville, John Currin, Erich Fischl, or the new Leipzig school painters -- see http://www.gagosian.com/artists/jenny-saville , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jenny_Saville , http://www.gagosian.com/artists/john-currin , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Currin , http://www.ericfischl.com , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Fischl , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Leipzig_School , and http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/08/magazine/08leipzig.html?pagewanted=all . Although Jenny Saville has technical competence second to none, her paintings also have conceptual and thematic content that is interesting and contemporary. Her paintings could only have been created today, not in 1920, nor in 1820:

[video=vimeo;46612357]https://vimeo.com/46612357[/video] [video=vimeo;49767964]https://vimeo.com/49767964[/video]

Jump ahead in the first video 2 minutes, to get to the interview; in the second video, 45 seconds to get to the paintings; and in the third, 2 minutes, 20 seconds to get to the interview.

Mind you, I do not necessarily like the thematic content of Jenny Saville's work, even if it is recognizably contemporary and interesting. In her earlier work, Jenny Saville's content could be summarized as plastic surgery, fat, nudity, + blood; and in her later work, transgendering, drug and other kinds of abuse, + nudity. In John Currin, the thematic content is adolescent male fantasies of impossibly thin women with ridiculously oversized breasts. In Erich Fischl, it's nudity, middle-class suburban angst, + taboos. If this is what it means to truly paint the "Zeitgesit", then our contemporary Zeitgeist is wretched.

Here I might mention that I see no reason why any artist should ever feel obligated to paint "the Zeitgeist" (whatever that might be....), nor obligated to invest their work with novel, transgressive content that has not been explored before, merely to signal the "contemporary" nature of their calling. Some themes really are timeless and universal, and there should be nothing wrong with creating a contemporary painting whose theme is "The Kiss", for instance, even though this has been done hundreds of times before, by Klimt, Hayez, Rodin, and others -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kiss_(Klimt) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kiss_(Hayez) , and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kiss_(Rodin_sculpture) . It is a mistake to think that contemporary figurative work must have quasi-porographic, transgressive content, as per the rough-trade photographs of Joel Peter Watkin or Robert Mapplethorpe, just in order to read as contemporary (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joel-Peter_Witkin , Joel Peter Witkin , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Mapplethorpe , Robert Mapplethorpe (men) , and Robert Mapplethorpe (whip) ; warning: these images are hard to stomach!!).

********************************************

6. The Zeitgeist is Never Right

********************************************

Furthermore, I've always been a bit skeptical of the value-judgments implicit in most Art-historical periodizations, and most Art-historical forms of aesthetic explanation and justification. Personally, I have little time or patience for neo-Heglian,“The Zeitgeist is Always Right” pseudo-argumentation, i.e. of the kind that passes for aesthetic philosophy amongst most contemporary Art historians and Art critics. I got into some real fights with a good friend of mine who still teaches Art History in Switzerland over precisely this issue. While he was teaching respect for canonical modernist Art History in the Humanities building, I was simultaneously teaching my painting and sculpture students the exact opposite in the Fine Arts complex. I taught my students that any established art-historical canon is a target just waiting to be attacked, especially the standard 19th and 20[SUP]th[/SUP] centuries' secular-triumphalist narratives of increasingly cerebral avant-garde “isms”, fighting the good fight against supposedly philistine bourgeois taste.

When Art Historians teach their students that the Art of the late 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century was dominated by a succession of avant-garde movements, beginning with Impressionism, and then running through Pointilism, Symbolism, Post-Impressionism, etc., they are reading the 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century in a very anachronistic way. The late 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century only “looks” Impressionistic in hindsight, from the vantage point of an Art Historian politically committed to Modernism in Art, say, circa 1960. But the late 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century did not see itself this way at all. The vast majority of artistic output from 1870 to 1900 was still neo-classical Beaux-Arts figuration -- see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academic_art , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neoclassicism , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/École_nationale_supérieure_des_Beaux-Arts , http://www.jssgallery.org/Essay/Ecole_des_Beaux-Arts/Ecole_des_Beaux-Arts.htm , and http://www.culture.gouv.fr/ENSBA/History.html , http://www.ensba.fr/ .

Once one begins investigating matters empirically for oneself, the actual "facts" of Art History are usually messier and considerably at odds with the canonical readings that Art Historians have constructed. For instance, at the largest Paris Salon of 1900 most of the work on display still demonstrated superb traditional figurative training. Maybe half the canvases were in the Beaux-Arts tradition of classical figuration (think Bougereau, who was still much sought-after in 1900, and died only in 1905 – again, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William-Adolphe_Bouguereau and http://www.artrenewal.org/pages/artist.php?artistid=7 ); another 30 % of the canvases were notionally “symbolist”, but still highly skilled; and the remaining 20 % of the canvases were Impressionist landscapes, a movement that by then was enjoying economic success and more widespread acceptance. I am basing this estimate on the contents of various books that I've come across over the years, books that provide complete catalogs of the paintings that actually hung on the walls of the Paris salons from 1895 to 1907 -- see for instance https://www.croquelinottes.fr/livre...ociete-nationa--gaite-dugnat-echelle-de-jacob , https://www.croquelinottes.fr/livre...ociete-nationa--gaite-dugnat-echelle-de-jacob , http://www.amazon.com/French-Artists-1800-1900-Richard-Brettell/dp/0810909464/ref=sr_1_8?s=books , http://www.amazon.com/End-Salon-State-Early-Republic/dp/0521432510/ref=sr_1_28?s=books, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salon_(Paris) , and http://nga.gov.au/Research/Salons.cfm .

In the early 1900's Gaugin and Van Gogh were still a very avant-garde, minority taste, and even more so “Le Fauves” – in effect, proto-Expressionists – who hit the scene only circa 1904 to 1908 – see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fauvism . Notably Piccaso’s earliest work during this period is best classified as pictorially and thematically conservative “symbolism” -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picasso's_Blue_Period and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picasso's_Rose_Period . No doubt Picasso first painted in a symbolist manner because that's what all the other young artists were doing at the time. Over in England, the pre-Raphaelites and those they inspired completely dominated the Victorian and Edwardian Art markets, even though only 30 years later (circa 1930), with the latest avant-garde movements spilling over from the continent, you could be forgiven for never having heard of the pre-Raphaelites. Like their social-Realist and Symbolist counterparts on the continent, the pre-Raphaelites were superbly skilled figurative painters – seehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pre-Raphaelite_Brotherhood . The Ashmoleon museum in Oxford has a number of rooms dedicated to their work -- see https://dantisamor.wordpress.com/2015/05/13/pre-raphaelites-at-the-ashmolean-great-british-drawings/ and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashmolean_Museum :

[video=youtube;EVef690js9g]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVef690js9g [/video]

The only Art History book I've yet come across which acknowledges just how conservatively "academic" and "figurative" most French Art still was in 1900, and how much Art in 1900 was politically contested territory, is Fae Bauer's very recent Rivals and Conspirators -- see http://www.amazon.com/Rivals-Conspi...ntre/dp/1443853763/ref=sr_1_6?s=books&ie=UTF8 . Generations of Art History students have mistakenly imagined that in late 19th century successful Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters dominated the Paris Art World. But the truth is otherwise, and the fin-de-siecle only looks radical, revolutionary, and bohemian in hindsight:

The fact that most people have never heard of the second list of painters says more about how Art History is a fictional construct, than it says anything about the artistic merit of these artists per se.

My good friend in Switzerland always positively hated such observations, even though he could not refute them, because they are empirical observations, matters of fact, and undeniably true. He suggested that I was perversely defying the agreed Modernist “canon”, and that I was reading Modern Art History in an aberrant, revisionist sort of way, one that would only “confuse students”. Needless to say, guilty as charged. It was precisely my aim to encourage students to think for themselves, in relation to social constructions like the canonical, Whig history of Modernist Art. And to encourage them to wonder what kinds of closet political agendas Modernist Art Historians might be pushing, when they depicted Paris as awash with Impressionism, circa 1880, or even circa 1900. When in actual fact neoclassical academic Art dominated most of the 19th century, right up to and including 1900.

On my own view, even when critics and Art Historians judge very innovative work as having artistic merit, they too do not use a temporal, historical yardstick, but rather, they judge such work deserving because even if only implicitly, they measure it using a-temporal, non-historical, timeless standards. Put simply, Monet, Renoir, Manet, and Degas really could draw. So even if their handling of color and tone was unconventional, and their subject matter contemporary and non-allegorical, there is a quality to their work that is not only trans-historical, but also trans-cultural. How else to explain the universal appeal of Impressionism amongst Chinese and Japanese collectors, for instance? Of vice-versa: how else to explain the ability of western collectors to make sound aesthetic judgments about the quality of diverse forms of Asian art?

Or how else to explain the manner in which the Art Historical "canon" has been revised over the centuries, with the rehabilitation of previously neglected artists like Rembrandt and Botticelli? For about 150 years after his death Rembrandt's work was thought too crude, badly drawn, and insufficiently classical to be worthy of emulation, while Botticell's work was seen as late Gothic and not early Renaissance. Rembrandt's reputation only began to improve in the 1700s, and then massively so in the 1800s, while Botticelli's paintings were only finally appreciated in the late 19th century -- see http://www.artnews.com/2006/07/01/rembrandt-myth-legend-truth/ , http://dare.uva.nl/cgi/arno/show.cgi?fid=133234 , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sandro_Botticelli , and http://www.artble.com/artists/sandro_botticelli . The "fungible", somewhat fictitious and constructed nature of the Art-historical canon is a dirty little secret that Art Historians try to evade and paper-over. Typically one needs to be enrolled in a graduate program before one's teachers are willing to discuss such uncomfortable facts openly. Mind you, I don't think the canon is completely fictitious and constructed, because I do believe that "timeless standards" exist. But amongst those standards, mere "novelty" should be one our less important aesthetic concerns, and it really should not matter whether a given artist was "the first" to do x, y, or z. After a few centuries any purely temporal significance that a given painting, sculpture, or body of work may have had fades into insignificance, and who-did-what-first remains interesting only to Art Historians. What matters to everyone else is the quality of the work itself.

For specialists in Graeco-Roman Art History things are even harder, because most of the sculpture that we have in marble are Roman copies of earlier Greek bronzes, and the dating of most pieces is highly speculative and contentious. So it's very difficult to assess the historical significance of any given piece, if one cannot even construct a non-contentious time-line. But this is not really a problem, because those of us who are not professional Art Historians are happy to instead just enjoy the quality of ancient Greaco-Roman sculpture appreciated a-historically.

Of course saying all of this robs Art Historians of their particular claim to authority, namely, their mastery of the dates and details of Art history. As such, it suggests that their role as "gatekeepers" of what should and should not be considered artistically worthwhile is open to debate. Even if we do not know how a given piece or body of work fits into their constructed narratives, we are nonetheless still free to make our own aesthetic judgements. One does not need a degree in Art History in order to judge the Apollo Belvedere, Botticelli's Allegory of Spring, Rembrandt's Jewish Bride, or the Mark Rothko's chapel in Houston, to be very beautiful works of Art -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_Belvedere , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primavera_(painting) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Jewish_Bride, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rothko_Chapel , http://www.rothkochapel.org , and Rothko Chapel .

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

4. The stupidity of remaining merely traditional......

********************************************

However, with that said, simultaneously I think it's just willfully ignorant to paint in 2016 as if one were living in 1816. It's both aesthetically and politically reactionary to paint as if the visual and conceptual innovations of the 20th century never happened. In 2003 a review appeared in the New York Times of student work produced at the Florence Academy of Art, and described such work as "… inertly composed still lifes, laughable allegories and preciously romantic self-portraits ... glazed by decades of exposure to tobacco smoke." See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Academy_of_Art , http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/12/a...sm-revisited-the-florence-academy-of-art.html , http://www.florenceacademyofart.com , and http://www.florenceacademyofart.com/en/student-gallery/ . I've taken a few summer courses at the Florence Academy, and this is an accurate description.

Although I do admire the skill of "New Classical" painters associated with the ARC, the Florence Academy, and the New York Academy, perhaps because I am also a trained philosopher, their work almost always leaves me unsatisfied in terms of content. Mere demonstration of artisanal skill is not enough, but unfortunately most of those engaged in “New Classicism” seem to demonstrate little else. Referring back to the ARC website, take a look through some of the portfolios of the best currently practicing “Living Masters” painters – see http://www.artrenewal.org/pages/livingartists.php . Although artisanal skill has returned – and then some – spiritually or intellectually satisfying content is mostly missing. Most of their paintings are single-figure compositions, or even worse, mere portraits, and it’s always hard to suggest an interesting narrative with just one figure.

What's most obviously missing in such paintings is a “will to expression”: a will to depict humans for some specific reason, because the artist wants to say something about the kinds of creatures that we humans are. Pre-19th century figurative Art always expressed values that were much larger than the Art World itself, so there is a certain irony in how New Classical painters make mere demonstration of traditional painterly skill "the main event". As per modern Abstract-expressionist painters, the "how", the mark-making, the painterly precision and/or bravura, becomes an end in itself. Content becomes irrelevant, and all that matters is Art for Art's sake. Although New Classicists like to imagine themselves reviving pre-modern figuration, given their focus on form instead of substance, and given the absence of truly interesting content in most of their work, their sensibility seems modernist to the core. They are reviving merely the husk, the shell of the pre-modern figurative tradition; they are reviving mere style and technique. Their paintings then become little more than fetish-objects demonstrating consummate life-drawing and life-painting skill; they become mere egocentric, self-referential manifestations of painterly prowess. But such paintings don't actually say anything, they don't "speak" to viewers in a meaningful or significant way.

To put the point most forcefully: if these artists really did want to say something, they would show more willingness to take up the challenge of multi-figure, narrative composition. Because whenever one puts two or more figures into a painting, even if one did not intend a narrative meaning, viewers will try to find one. If such "academic" or "New Classical" artists were truly interested in communicating with viewers and expressing something, they would recognize that the most important traditional figurative painting has always been multi-figure historical or religious allegory. Mere single-figure portraits never had much status, because they lacked the kind of intellectual and spiritual content that can only be communicated through the use of multiple figures.

********************************************

5. And yet the danger of becoming merely a creature of one's time......

********************************************

Now there is a huge difference between the output of such "academic" or "New Classical" artists featured on Art Renewal's website, versus the work of contemporary figurative artists like Jenny Saville, John Currin, Erich Fischl, or the new Leipzig school painters -- see http://www.gagosian.com/artists/jenny-saville , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jenny_Saville , http://www.gagosian.com/artists/john-currin , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Currin , http://www.ericfischl.com , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Fischl , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Leipzig_School , and http://www.nytimes.com/2006/01/08/magazine/08leipzig.html?pagewanted=all . Although Jenny Saville has technical competence second to none, her paintings also have conceptual and thematic content that is interesting and contemporary. Her paintings could only have been created today, not in 1920, nor in 1820:

[video=vimeo;46612357]https://vimeo.com/46612357[/video] [video=vimeo;49767964]https://vimeo.com/49767964[/video]

Jump ahead in the first video 2 minutes, to get to the interview; in the second video, 45 seconds to get to the paintings; and in the third, 2 minutes, 20 seconds to get to the interview.

Mind you, I do not necessarily like the thematic content of Jenny Saville's work, even if it is recognizably contemporary and interesting. In her earlier work, Jenny Saville's content could be summarized as plastic surgery, fat, nudity, + blood; and in her later work, transgendering, drug and other kinds of abuse, + nudity. In John Currin, the thematic content is adolescent male fantasies of impossibly thin women with ridiculously oversized breasts. In Erich Fischl, it's nudity, middle-class suburban angst, + taboos. If this is what it means to truly paint the "Zeitgesit", then our contemporary Zeitgeist is wretched.

Here I might mention that I see no reason why any artist should ever feel obligated to paint "the Zeitgeist" (whatever that might be....), nor obligated to invest their work with novel, transgressive content that has not been explored before, merely to signal the "contemporary" nature of their calling. Some themes really are timeless and universal, and there should be nothing wrong with creating a contemporary painting whose theme is "The Kiss", for instance, even though this has been done hundreds of times before, by Klimt, Hayez, Rodin, and others -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kiss_(Klimt) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kiss_(Hayez) , and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Kiss_(Rodin_sculpture) . It is a mistake to think that contemporary figurative work must have quasi-porographic, transgressive content, as per the rough-trade photographs of Joel Peter Watkin or Robert Mapplethorpe, just in order to read as contemporary (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joel-Peter_Witkin , Joel Peter Witkin , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Mapplethorpe , Robert Mapplethorpe (men) , and Robert Mapplethorpe (whip) ; warning: these images are hard to stomach!!).

********************************************

6. The Zeitgeist is Never Right

********************************************

Furthermore, I've always been a bit skeptical of the value-judgments implicit in most Art-historical periodizations, and most Art-historical forms of aesthetic explanation and justification. Personally, I have little time or patience for neo-Heglian,“The Zeitgeist is Always Right” pseudo-argumentation, i.e. of the kind that passes for aesthetic philosophy amongst most contemporary Art historians and Art critics. I got into some real fights with a good friend of mine who still teaches Art History in Switzerland over precisely this issue. While he was teaching respect for canonical modernist Art History in the Humanities building, I was simultaneously teaching my painting and sculpture students the exact opposite in the Fine Arts complex. I taught my students that any established art-historical canon is a target just waiting to be attacked, especially the standard 19th and 20[SUP]th[/SUP] centuries' secular-triumphalist narratives of increasingly cerebral avant-garde “isms”, fighting the good fight against supposedly philistine bourgeois taste.

When Art Historians teach their students that the Art of the late 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century was dominated by a succession of avant-garde movements, beginning with Impressionism, and then running through Pointilism, Symbolism, Post-Impressionism, etc., they are reading the 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century in a very anachronistic way. The late 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century only “looks” Impressionistic in hindsight, from the vantage point of an Art Historian politically committed to Modernism in Art, say, circa 1960. But the late 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century did not see itself this way at all. The vast majority of artistic output from 1870 to 1900 was still neo-classical Beaux-Arts figuration -- see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academic_art , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neoclassicism , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/École_nationale_supérieure_des_Beaux-Arts , http://www.jssgallery.org/Essay/Ecole_des_Beaux-Arts/Ecole_des_Beaux-Arts.htm , and http://www.culture.gouv.fr/ENSBA/History.html , http://www.ensba.fr/ .

Once one begins investigating matters empirically for oneself, the actual "facts" of Art History are usually messier and considerably at odds with the canonical readings that Art Historians have constructed. For instance, at the largest Paris Salon of 1900 most of the work on display still demonstrated superb traditional figurative training. Maybe half the canvases were in the Beaux-Arts tradition of classical figuration (think Bougereau, who was still much sought-after in 1900, and died only in 1905 – again, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William-Adolphe_Bouguereau and http://www.artrenewal.org/pages/artist.php?artistid=7 ); another 30 % of the canvases were notionally “symbolist”, but still highly skilled; and the remaining 20 % of the canvases were Impressionist landscapes, a movement that by then was enjoying economic success and more widespread acceptance. I am basing this estimate on the contents of various books that I've come across over the years, books that provide complete catalogs of the paintings that actually hung on the walls of the Paris salons from 1895 to 1907 -- see for instance https://www.croquelinottes.fr/livre...ociete-nationa--gaite-dugnat-echelle-de-jacob , https://www.croquelinottes.fr/livre...ociete-nationa--gaite-dugnat-echelle-de-jacob , http://www.amazon.com/French-Artists-1800-1900-Richard-Brettell/dp/0810909464/ref=sr_1_8?s=books , http://www.amazon.com/End-Salon-State-Early-Republic/dp/0521432510/ref=sr_1_28?s=books, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salon_(Paris) , and http://nga.gov.au/Research/Salons.cfm .

In the early 1900's Gaugin and Van Gogh were still a very avant-garde, minority taste, and even more so “Le Fauves” – in effect, proto-Expressionists – who hit the scene only circa 1904 to 1908 – see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fauvism . Notably Piccaso’s earliest work during this period is best classified as pictorially and thematically conservative “symbolism” -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picasso's_Blue_Period and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picasso's_Rose_Period . No doubt Picasso first painted in a symbolist manner because that's what all the other young artists were doing at the time. Over in England, the pre-Raphaelites and those they inspired completely dominated the Victorian and Edwardian Art markets, even though only 30 years later (circa 1930), with the latest avant-garde movements spilling over from the continent, you could be forgiven for never having heard of the pre-Raphaelites. Like their social-Realist and Symbolist counterparts on the continent, the pre-Raphaelites were superbly skilled figurative painters – seehttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pre-Raphaelite_Brotherhood . The Ashmoleon museum in Oxford has a number of rooms dedicated to their work -- see https://dantisamor.wordpress.com/2015/05/13/pre-raphaelites-at-the-ashmolean-great-british-drawings/ and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashmolean_Museum :

[video=youtube;EVef690js9g]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVef690js9g [/video]

The only Art History book I've yet come across which acknowledges just how conservatively "academic" and "figurative" most French Art still was in 1900, and how much Art in 1900 was politically contested territory, is Fae Bauer's very recent Rivals and Conspirators -- see http://www.amazon.com/Rivals-Conspi...ntre/dp/1443853763/ref=sr_1_6?s=books&ie=UTF8 . Generations of Art History students have mistakenly imagined that in late 19th century successful Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters dominated the Paris Art World. But the truth is otherwise, and the fin-de-siecle only looks radical, revolutionary, and bohemian in hindsight:

Despite the renown today of Neo-Impressionism, Art Nouveau, Fauvism, Cubism and Orphism, the most powerful artists in this "modern art centre" were not Sonia Delaunay, Emile Galle, Paul Signac, Henri Matisse or even Picasso but such Academicians as Leon Bonnat, William Bouguereau, Fernand Cormon, Edouard Detaille, Gabriel Ferrier, Jean-Paul Laurens, Luc-Oliver Merson and Aime Morot, who exhibited at the "official" Salon supported by the machinery of the State.

The fact that most people have never heard of the second list of painters says more about how Art History is a fictional construct, than it says anything about the artistic merit of these artists per se.

My good friend in Switzerland always positively hated such observations, even though he could not refute them, because they are empirical observations, matters of fact, and undeniably true. He suggested that I was perversely defying the agreed Modernist “canon”, and that I was reading Modern Art History in an aberrant, revisionist sort of way, one that would only “confuse students”. Needless to say, guilty as charged. It was precisely my aim to encourage students to think for themselves, in relation to social constructions like the canonical, Whig history of Modernist Art. And to encourage them to wonder what kinds of closet political agendas Modernist Art Historians might be pushing, when they depicted Paris as awash with Impressionism, circa 1880, or even circa 1900. When in actual fact neoclassical academic Art dominated most of the 19th century, right up to and including 1900.

On my own view, even when critics and Art Historians judge very innovative work as having artistic merit, they too do not use a temporal, historical yardstick, but rather, they judge such work deserving because even if only implicitly, they measure it using a-temporal, non-historical, timeless standards. Put simply, Monet, Renoir, Manet, and Degas really could draw. So even if their handling of color and tone was unconventional, and their subject matter contemporary and non-allegorical, there is a quality to their work that is not only trans-historical, but also trans-cultural. How else to explain the universal appeal of Impressionism amongst Chinese and Japanese collectors, for instance? Of vice-versa: how else to explain the ability of western collectors to make sound aesthetic judgments about the quality of diverse forms of Asian art?

Or how else to explain the manner in which the Art Historical "canon" has been revised over the centuries, with the rehabilitation of previously neglected artists like Rembrandt and Botticelli? For about 150 years after his death Rembrandt's work was thought too crude, badly drawn, and insufficiently classical to be worthy of emulation, while Botticell's work was seen as late Gothic and not early Renaissance. Rembrandt's reputation only began to improve in the 1700s, and then massively so in the 1800s, while Botticelli's paintings were only finally appreciated in the late 19th century -- see http://www.artnews.com/2006/07/01/rembrandt-myth-legend-truth/ , http://dare.uva.nl/cgi/arno/show.cgi?fid=133234 , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sandro_Botticelli , and http://www.artble.com/artists/sandro_botticelli . The "fungible", somewhat fictitious and constructed nature of the Art-historical canon is a dirty little secret that Art Historians try to evade and paper-over. Typically one needs to be enrolled in a graduate program before one's teachers are willing to discuss such uncomfortable facts openly. Mind you, I don't think the canon is completely fictitious and constructed, because I do believe that "timeless standards" exist. But amongst those standards, mere "novelty" should be one our less important aesthetic concerns, and it really should not matter whether a given artist was "the first" to do x, y, or z. After a few centuries any purely temporal significance that a given painting, sculpture, or body of work may have had fades into insignificance, and who-did-what-first remains interesting only to Art Historians. What matters to everyone else is the quality of the work itself.

For specialists in Graeco-Roman Art History things are even harder, because most of the sculpture that we have in marble are Roman copies of earlier Greek bronzes, and the dating of most pieces is highly speculative and contentious. So it's very difficult to assess the historical significance of any given piece, if one cannot even construct a non-contentious time-line. But this is not really a problem, because those of us who are not professional Art Historians are happy to instead just enjoy the quality of ancient Greaco-Roman sculpture appreciated a-historically.

Of course saying all of this robs Art Historians of their particular claim to authority, namely, their mastery of the dates and details of Art history. As such, it suggests that their role as "gatekeepers" of what should and should not be considered artistically worthwhile is open to debate. Even if we do not know how a given piece or body of work fits into their constructed narratives, we are nonetheless still free to make our own aesthetic judgements. One does not need a degree in Art History in order to judge the Apollo Belvedere, Botticelli's Allegory of Spring, Rembrandt's Jewish Bride, or the Mark Rothko's chapel in Houston, to be very beautiful works of Art -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_Belvedere , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primavera_(painting) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Jewish_Bride, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rothko_Chapel , http://www.rothkochapel.org , and Rothko Chapel .

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

.

Last edited:

biotect

Designer

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

7. The Limited Shelf-Life of Mere Shock Art

********************************************

Stepping back a bit, the problem for modern and contemporary Art seems to be this. What began amongst Art Historians as merely descriptive tool to categorize work -- the lumping together of work in "periods", and giving those periods names such as "Archaic", "Classical", "Hellenistic", "Early Renaissance", "Mannerist", "Baroque", etc. -- morphed into something one might call "movement self-consciousness". A purely descriptive, empirical exercise in Art-Historical categorization, transformed in the 19th century into a normative demand that to be significant, a painter had to be part of a movement that could be considered "progressive" when situated inside a single, unilinear metanarrative of western Art History. If work could not be classified as emblematic of a progressive movement, then it had no merit. All sorts of questionable presuppositions were loaded into this view, for instance, the notion that there can even be such a thing as "progress" in the visual Arts. There can certainly be "progress" in Science and Mathematics. But does it make any sense to say that there can be "progress" in literature, or painting? And if there cannot, then why should mere novelty or "shock potential" come to be considered the primary or even the sole aesthetic value?

When mere "shock potential" comes to be seen as the sole aesthetic value, we should not be too surprised when the Art World produces works like Andre Serrano's "Piss Christ", or the Abortion Project of Yale student Aliza Shvarts -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piss_Christ , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andres_Serrano , http://andresserrano.org , http://www.artnet.com/usernet/awc/a...202827&gid=424202827&cid=74183&works_of_art=1 , http://www.artnet.com/usernet/awc/a...&gid=424202827&cid=74183&wid=425106388&page=1 , http://www.saatchigallery.com/aipe/andres_serrano.htm , http://bombmagazine.org/article/1631/andres-serrano ,http://www.theguardian.com/world/20...no-piss-christ-destroyed-christian-protesters , http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/sep/28/andres-serrano-piss-christ-new-york , http://www.christianpost.com/news/p...offensive-charlie-hebdo-islam-cartoon-132289/ , and http://www.huffingtonpost.com/news/piss-christ/ ; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yale_student_abortion_art_controversy , http://www.alizashvarts.com/a_a_a_aaa/_....html , http://www.alizashvarts.com/a_a_a_aaa/_......html , http://www.alizashvarts.com/a_a_a_aaa/_..........html , http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/04/17/AR2008041702519.html , http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/19/arts/design/19arts-CONTROVERSYO_BRF.html?_r=0 , and http://www.foxnews.com/story/2008/0...roject-is-real-despite-university-claims.html :

In the case of Andes Serrano I am inclined to be somewhat forgiving, because his photographic skills are quite exceptional and "classical". Immediately following the "Piss Christ" controversy, Sister Wendy Beckett (a famous British nun who writes about Art) expressed her support, and the Catholic church commissioned Serrano to do a wonderful series of portraits of monks, priests, and nuns, his "Church" series -- see http://bcjesus.weebly.com/jesusart-ii.html and http://www.artnet.com/usernet/awc/a...02827&gid=424202827&cid=121350&works_of_art=1 :

Personally, I am also a fan of Serrano's "Morgue" series: enormous, classically composed Cibachromes that are very respectful of the dead -- see http://beautifuldecay.com/2013/09/13/andres-serranos-powerful-images-death/ , http://laquariumdesign.canalblog.co...otos/8722737-andres_serrano__the_morgue_.html , and http://www.artnet.com/usernet/awc/a...02827&gid=424202827&cid=118026&works_of_art=1 :

As a mere publicity stunt to gain attention at the outset of one's career "shock art" might be forgiven. But if an artist can't move beyond that, there is a danger that their subsequent work will become mere self-quoting cliché.

History suggests that a young artist may be setting themselves up for disappointment if their initial success in the Art World depends merely upon some historically novel but superficial gimmick -- a gimmick in terms of form, content, or both -- but a gimmick with a short shelf life, soon to become yesterday's news. The danger is that after initial success as an "exemplar" of the contemporary Zeitgeist, there may be few logical or authentic paths available that continue along the same trajectory. It may then prove difficult to truly build upon and organically evolve derivations of the original breakthrough. Here I am thinking not just of a "shock artist" like Andres Serrano, but also of now-canonical artists like Roy Lichtenstein and Frank Stella -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Lichtenstein and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Stella . The earliest breakthrough work of Lichtenstein and Stella now commands the highest prices, whereas their most recent and supposedly most "mature" work holds the least interest, and is the least expensive -- see http://www.amazon.co.uk/Talking-Prices-Contemporary-Princeton-Sociology/dp/0691134030 , http://press.princeton.edu/titles/8035.html , http://www.uva.nl/over-de-uva/organisatie/medewerkers/content/v/e/o.j.m.velthuis/o.j.m.velthuis.html , and http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Value-Art-Money-Beauty/dp/3791349139/ref=pd_sim_14_5/276-7199516-5377469 .

Putting the point very broadly, worship of the false gods that one mistakenly imagines dominate the current -- or for that matter any, Zeitgeist -- may have negative career implications, in so far as "He who marries the spirt of an age, will soon find themselves a widower".

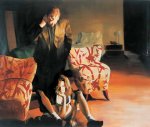

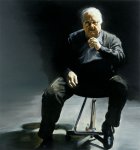

By way of contrast, it must be granted that Eric Fischl has had a very long and successful run, lasting a lifetime. Perhaps because Fischl's figurative skill has steadily improved, year after year, his most recent paintings often sell for more than the older work. Jenny Saville and John Currin seem set to accomplish the same. Not all of Fischl's work traffics in perversion and taboo, and some of his later work can be quite beautiful, at least in purely "formal" terms. Like Jenny Saville, Fischl now really knows how to paint, and details like dress and furniture are convincingly contemporary. 300 years ago, we simply did not have the super-saturated dyes that have made red-patterned upholstery of this kind possible, nor did people dress in "all-black formal/casual chic", because they are important figures in the New York art world. In the first video, skip ahead 5 minutes, 30 seconds to get to the part where Eric Fischl begins talking, and in the second, 5 minutes 15 seconds to get to the interesting part where Steven Martin and Eric Fischl begin talking:

Furthermore, right from the very beginning of his Art career Fischl has had the courage to populate his canvases with multiple figures, in some early paintings as many as 5 or 6 -- see http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/13/arts/design/eric-fischl-early-paintings.html?_r=0 , http://www.ericfischl.com/html/en/paintings/early1_82_029.html , http://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/artpages/eric_fischl_2.htm , Eric Fischl -- The old man's boat and the old man's dog , http://www.ericfischl.com/html/en/paintings/early1_82_031.html , Eric Fischl -- Barbecue , http://www.ericfischl.com/html/en/paintings/early1_82_028.html , Eric Fischl -- St. Tropez , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dfe43lhdnsM , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JD3Koe1PsaQ , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUnntJLMMlQ , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xX9iE1r2mGw , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4gL5sx5C4f8 , and http://www.wnyc.org/story/310091-eric-fischl/ . Although his technique in these early paintings is really quite awful, at least Fischl was trying to say something.

Whether it was actually worth saying, is a different question. In terms of content, who knows exactly how posterity will evaluate the work of Saville, Fischl, Currin, et al, and judge the spirit of the late 20th century that their work supposedly mirrors?

In the case of Fischl in particular, although his earliest work could definitely be described as "shock Art", to his credit Fischl had the intelligence and foresight to realize that he could not continue capitalizing on mere shock alone. In his later work his themes as well as his technique became more mature, refined, and nuanced. Currin and Saville would be wise to follow his example, and discover ways to adjust their content accordingly.....:ylsmoke:

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

.

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

7. The Limited Shelf-Life of Mere Shock Art

********************************************

Stepping back a bit, the problem for modern and contemporary Art seems to be this. What began amongst Art Historians as merely descriptive tool to categorize work -- the lumping together of work in "periods", and giving those periods names such as "Archaic", "Classical", "Hellenistic", "Early Renaissance", "Mannerist", "Baroque", etc. -- morphed into something one might call "movement self-consciousness". A purely descriptive, empirical exercise in Art-Historical categorization, transformed in the 19th century into a normative demand that to be significant, a painter had to be part of a movement that could be considered "progressive" when situated inside a single, unilinear metanarrative of western Art History. If work could not be classified as emblematic of a progressive movement, then it had no merit. All sorts of questionable presuppositions were loaded into this view, for instance, the notion that there can even be such a thing as "progress" in the visual Arts. There can certainly be "progress" in Science and Mathematics. But does it make any sense to say that there can be "progress" in literature, or painting? And if there cannot, then why should mere novelty or "shock potential" come to be considered the primary or even the sole aesthetic value?

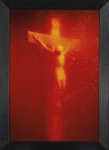

When mere "shock potential" comes to be seen as the sole aesthetic value, we should not be too surprised when the Art World produces works like Andre Serrano's "Piss Christ", or the Abortion Project of Yale student Aliza Shvarts -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piss_Christ , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andres_Serrano , http://andresserrano.org , http://www.artnet.com/usernet/awc/a...202827&gid=424202827&cid=74183&works_of_art=1 , http://www.artnet.com/usernet/awc/a...&gid=424202827&cid=74183&wid=425106388&page=1 , http://www.saatchigallery.com/aipe/andres_serrano.htm , http://bombmagazine.org/article/1631/andres-serrano ,http://www.theguardian.com/world/20...no-piss-christ-destroyed-christian-protesters , http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/sep/28/andres-serrano-piss-christ-new-york , http://www.christianpost.com/news/p...offensive-charlie-hebdo-islam-cartoon-132289/ , and http://www.huffingtonpost.com/news/piss-christ/ ; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yale_student_abortion_art_controversy , http://www.alizashvarts.com/a_a_a_aaa/_....html , http://www.alizashvarts.com/a_a_a_aaa/_......html , http://www.alizashvarts.com/a_a_a_aaa/_..........html , http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/04/17/AR2008041702519.html , http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/19/arts/design/19arts-CONTROVERSYO_BRF.html?_r=0 , and http://www.foxnews.com/story/2008/0...roject-is-real-despite-university-claims.html :

In the case of Andes Serrano I am inclined to be somewhat forgiving, because his photographic skills are quite exceptional and "classical". Immediately following the "Piss Christ" controversy, Sister Wendy Beckett (a famous British nun who writes about Art) expressed her support, and the Catholic church commissioned Serrano to do a wonderful series of portraits of monks, priests, and nuns, his "Church" series -- see http://bcjesus.weebly.com/jesusart-ii.html and http://www.artnet.com/usernet/awc/a...02827&gid=424202827&cid=121350&works_of_art=1 :

Personally, I am also a fan of Serrano's "Morgue" series: enormous, classically composed Cibachromes that are very respectful of the dead -- see http://beautifuldecay.com/2013/09/13/andres-serranos-powerful-images-death/ , http://laquariumdesign.canalblog.co...otos/8722737-andres_serrano__the_morgue_.html , and http://www.artnet.com/usernet/awc/a...02827&gid=424202827&cid=118026&works_of_art=1 :

As a mere publicity stunt to gain attention at the outset of one's career "shock art" might be forgiven. But if an artist can't move beyond that, there is a danger that their subsequent work will become mere self-quoting cliché.

History suggests that a young artist may be setting themselves up for disappointment if their initial success in the Art World depends merely upon some historically novel but superficial gimmick -- a gimmick in terms of form, content, or both -- but a gimmick with a short shelf life, soon to become yesterday's news. The danger is that after initial success as an "exemplar" of the contemporary Zeitgeist, there may be few logical or authentic paths available that continue along the same trajectory. It may then prove difficult to truly build upon and organically evolve derivations of the original breakthrough. Here I am thinking not just of a "shock artist" like Andres Serrano, but also of now-canonical artists like Roy Lichtenstein and Frank Stella -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Lichtenstein and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Stella . The earliest breakthrough work of Lichtenstein and Stella now commands the highest prices, whereas their most recent and supposedly most "mature" work holds the least interest, and is the least expensive -- see http://www.amazon.co.uk/Talking-Prices-Contemporary-Princeton-Sociology/dp/0691134030 , http://press.princeton.edu/titles/8035.html , http://www.uva.nl/over-de-uva/organisatie/medewerkers/content/v/e/o.j.m.velthuis/o.j.m.velthuis.html , and http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Value-Art-Money-Beauty/dp/3791349139/ref=pd_sim_14_5/276-7199516-5377469 .

Putting the point very broadly, worship of the false gods that one mistakenly imagines dominate the current -- or for that matter any, Zeitgeist -- may have negative career implications, in so far as "He who marries the spirt of an age, will soon find themselves a widower".

By way of contrast, it must be granted that Eric Fischl has had a very long and successful run, lasting a lifetime. Perhaps because Fischl's figurative skill has steadily improved, year after year, his most recent paintings often sell for more than the older work. Jenny Saville and John Currin seem set to accomplish the same. Not all of Fischl's work traffics in perversion and taboo, and some of his later work can be quite beautiful, at least in purely "formal" terms. Like Jenny Saville, Fischl now really knows how to paint, and details like dress and furniture are convincingly contemporary. 300 years ago, we simply did not have the super-saturated dyes that have made red-patterned upholstery of this kind possible, nor did people dress in "all-black formal/casual chic", because they are important figures in the New York art world. In the first video, skip ahead 5 minutes, 30 seconds to get to the part where Eric Fischl begins talking, and in the second, 5 minutes 15 seconds to get to the interesting part where Steven Martin and Eric Fischl begin talking:

Furthermore, right from the very beginning of his Art career Fischl has had the courage to populate his canvases with multiple figures, in some early paintings as many as 5 or 6 -- see http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/13/arts/design/eric-fischl-early-paintings.html?_r=0 , http://www.ericfischl.com/html/en/paintings/early1_82_029.html , http://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/artpages/eric_fischl_2.htm , Eric Fischl -- The old man's boat and the old man's dog , http://www.ericfischl.com/html/en/paintings/early1_82_031.html , Eric Fischl -- Barbecue , http://www.ericfischl.com/html/en/paintings/early1_82_028.html , Eric Fischl -- St. Tropez , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dfe43lhdnsM , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JD3Koe1PsaQ , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUnntJLMMlQ , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xX9iE1r2mGw , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4gL5sx5C4f8 , and http://www.wnyc.org/story/310091-eric-fischl/ . Although his technique in these early paintings is really quite awful, at least Fischl was trying to say something.

Whether it was actually worth saying, is a different question. In terms of content, who knows exactly how posterity will evaluate the work of Saville, Fischl, Currin, et al, and judge the spirit of the late 20th century that their work supposedly mirrors?

In the case of Fischl in particular, although his earliest work could definitely be described as "shock Art", to his credit Fischl had the intelligence and foresight to realize that he could not continue capitalizing on mere shock alone. In his later work his themes as well as his technique became more mature, refined, and nuanced. Currin and Saville would be wise to follow his example, and discover ways to adjust their content accordingly.....:ylsmoke:

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

.

Last edited:

biotect

Designer

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

8. A huge contrast: the lost Western tradition of idealistic, heroic figuration

********************************************

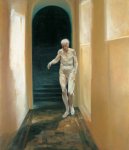

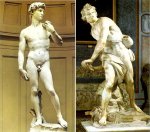

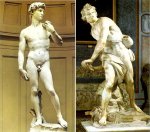

For me personally, the basic problem is that in none of these contemporary figurative painters does the human body express anything potentially transcendent or sublime. There is none of the "heroic nudity" one finds in Michelangelo's painting, Michelangelo's sculpture, Bernini's sculpture, and especially in ancient Graeco-Roman sculpture -- see https://artrenewal.org/articles/2012/Nudity/Nudity_Virtue_or_Vice.php , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heroic_nudity , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nude_(art) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Creation_of_Adam , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_(Michelangelo) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gian_Lorenzo_Bernini , http://www.artble.com/artists/gian_lorenzo_bernini , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_and_Daphne , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_and_Daphne_(Bernini) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_(Bernini) , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKzHdQKX9RA , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artemision_Bronze , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riace_bronzes , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doryphoros , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_Belvedere , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discobolus , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borghese_Gladiator , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laocoön , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pergamon_Altar , http://www.aviewoncities.com/gallery/showpicture.htm?key=kveit5558 , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Furietti_Centaurs , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dying_Gaul , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludovisi_Gaul , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boxer_at_Rest , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farnese_Hercules , http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=874 , http://www.louvre.fr/routes/heracles , https://plus.google.com/+JohnTrikeriotis/posts/GZq71AWFW6S , etc. etc.:

These last seven images are important examples of Graeco-Roman "heroic nudity", masterpieces not covered by the videos below. They are "Greaco-Roman" in the sense that all such sculpture could be considered, in truth, Greek. Even Roman copies of Greek originals were still in a sense Greek, because most of the sculptors employed by the Romans were Greeks: Greek slaves who attained an exceptional level of artistic skill. So "Roman" is for the most part a temporal designation. At one point, after various Roman wars on the Greek peninsula, more than half of Rome's population was Greek-speaking, and most upper-class Romans were bilingual, equally fluent in Latin and Greek.

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

8. A huge contrast: the lost Western tradition of idealistic, heroic figuration

********************************************

For me personally, the basic problem is that in none of these contemporary figurative painters does the human body express anything potentially transcendent or sublime. There is none of the "heroic nudity" one finds in Michelangelo's painting, Michelangelo's sculpture, Bernini's sculpture, and especially in ancient Graeco-Roman sculpture -- see https://artrenewal.org/articles/2012/Nudity/Nudity_Virtue_or_Vice.php , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heroic_nudity , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nude_(art) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Creation_of_Adam , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_(Michelangelo) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gian_Lorenzo_Bernini , http://www.artble.com/artists/gian_lorenzo_bernini , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_and_Daphne , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_and_Daphne_(Bernini) , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_(Bernini) , https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YKzHdQKX9RA , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artemision_Bronze , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riace_bronzes , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doryphoros , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apollo_Belvedere , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Discobolus , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borghese_Gladiator , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laocoön , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pergamon_Altar , http://www.aviewoncities.com/gallery/showpicture.htm?key=kveit5558 , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Furietti_Centaurs , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dying_Gaul , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludovisi_Gaul , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boxer_at_Rest , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Farnese_Hercules , http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=874 , http://www.louvre.fr/routes/heracles , https://plus.google.com/+JohnTrikeriotis/posts/GZq71AWFW6S , etc. etc.:

These last seven images are important examples of Graeco-Roman "heroic nudity", masterpieces not covered by the videos below. They are "Greaco-Roman" in the sense that all such sculpture could be considered, in truth, Greek. Even Roman copies of Greek originals were still in a sense Greek, because most of the sculptors employed by the Romans were Greeks: Greek slaves who attained an exceptional level of artistic skill. So "Roman" is for the most part a temporal designation. At one point, after various Roman wars on the Greek peninsula, more than half of Rome's population was Greek-speaking, and most upper-class Romans were bilingual, equally fluent in Latin and Greek.

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

Last edited:

biotect

Designer

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

Here are some excellent videos from the Khan Academy, videos that provide a survey of most of the highlights of the Greek classical, hellenistic, and Roman sculpture -- see https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/greek-art and https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman . They very effectively convey the values embodied in such sculpture, and the nobility and perfection that the Greeks thought human bodies could incarnate:

[video=youtube;TPM1LuW3Y5w]https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=157&v=TPM1LuW3Y5w[/video]

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

Here are some excellent videos from the Khan Academy, videos that provide a survey of most of the highlights of the Greek classical, hellenistic, and Roman sculpture -- see https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/greek-art and https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman . They very effectively convey the values embodied in such sculpture, and the nobility and perfection that the Greeks thought human bodies could incarnate:

[video=youtube;TPM1LuW3Y5w]https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=157&v=TPM1LuW3Y5w[/video]

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

Last edited:

biotect

Designer

...

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

9. Anti-Heroic, Anti-Transcendental Figurative Painting in the 20th Century

********************************************

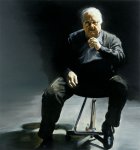

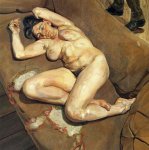

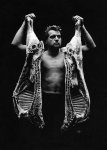

Put more broadly, painters like Jenny Saville, John Currin, and Eric Fischl have in a sense merely continued Lucien Freud's and Francis Bacon's anti-transcendental, anti-heroic, thoroughly 20th century program of painting the human body as "just a slab of meat" -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucian_Freud , http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/list.php?m=a&s=tu&aid=1606 , http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/lucian-freud , http://www.boston.com/ae/theater_ar...eciating_lucian_freud_the_painter_the_friend/ , http://vernissage.tv/2010/03/25/lucian-freud-latelier-the-studio-centre-pompidou-paris/ , Lucien Freud , and Lucien Freud (full figure paintings) :

The first and then ninth images are self-portraits, and yes, the tenth image is you-know-who.....:coffeedrink:

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

9. Anti-Heroic, Anti-Transcendental Figurative Painting in the 20th Century

********************************************

Put more broadly, painters like Jenny Saville, John Currin, and Eric Fischl have in a sense merely continued Lucien Freud's and Francis Bacon's anti-transcendental, anti-heroic, thoroughly 20th century program of painting the human body as "just a slab of meat" -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucian_Freud , http://www.the-athenaeum.org/art/list.php?m=a&s=tu&aid=1606 , http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/lucian-freud , http://www.boston.com/ae/theater_ar...eciating_lucian_freud_the_painter_the_friend/ , http://vernissage.tv/2010/03/25/lucian-freud-latelier-the-studio-centre-pompidou-paris/ , Lucien Freud , and Lucien Freud (full figure paintings) :

The first and then ninth images are self-portraits, and yes, the tenth image is you-know-who.....:coffeedrink:

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

Last edited:

biotect

Designer

...

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

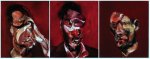

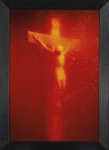

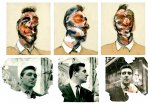

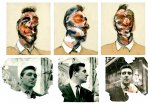

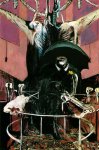

For Francis Bacon, see http://monoskop.org/images/1/1f/Deleuze_Gilles_Francis_Bacon_The_Logic_of_Sensation.pdf , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon_(artist) , http://francis-bacon.com/artworks/paintings , and Francis Bacon (works) :

*******************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

For Francis Bacon, see http://monoskop.org/images/1/1f/Deleuze_Gilles_Francis_Bacon_The_Logic_of_Sensation.pdf , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon_(artist) , http://francis-bacon.com/artworks/paintings , and Francis Bacon (works) :

*******************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

Last edited:

biotect

Designer

...

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

I included a surplus of images of Bacon's work, because even though I do not like his content, at the purely "formal" level I like how his paintings look, the triptychs in particular. Francis Bacon's combination of geometry, intense color, and more organic figurative elements is very original, very beautiful, and for reasons that I do not understand, has not been taken further by contemporary figurative painters. The only thing that ruins it for me, is that once one learns the details of Bacon's biography, one realizes that in some of his paintings the figures are basically naked homosexual men fighting or bonking, or both.

It was Francis Bacon who verbally stated that he saw human bodies as "just slabs of meat", but Lucien Freud much more explicitly painted them as such, and Jenny Saville all the more so. Freud even managed to turn the Queen's head into nothing more than a shriveled egg, even though she sat patiently for her portrait for months (yes, it was commissioned, and no doubt cost a fortune.....:Wow1 . Jenny Saville has openly acknowledged Lucien Freud as a precedent, and some critics have summarized Saville's work as "Lucien Freud + feminism".

. Jenny Saville has openly acknowledged Lucien Freud as a precedent, and some critics have summarized Saville's work as "Lucien Freud + feminism".

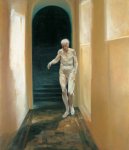

At the thematic level there's more going in Frischl's paintings than the mere alla-prima representation of human corporeality, because unlike Freud's paintings, Fischl's paintings usually have multiple figures, thereby encouraging a narrative reading; even if any narrative that Fischl may have intended remains deliberately indeterminate. But like Freud, Fischl does not have much training in classical figurative drawing and painting, and to some extent he is self-taught. So Fischl's figures and portraits are never very refined, some elements are mal-proportioned, and he does not idealize, happy to convey the full realistic ugliness of the people he represents, even in portraits. For instance, Fischl's full-length portrait of his gallerist, Mary Boone, depicts the face of an old, very difficult woman who apparently is not that nice. In the painting her face is much uglier than she appears in photographs, and her face in the painting when seen first-hand is even uglier still than in reproduction. I could not find an image on-line, so I'll leave it at that.

Whether Freud and Fischl have consciously chosen "realism" as an aesthetic, or whether they paint realistic ugliness because they do not have much choice, lacking the skill to represent figures as more beautiful and refined, is an open question. Whereas Saville most definitely has the classical training, so there is a strange battle in her work between the consummate formal beauty of her technique, her mark-making and use of color, her control of tone and bravura planar painting, versus the ugliness of her content. In Saville's case anti-idealistic, anti-heroic "realism" seems much more of a choice. Whether that makes her choice brave or lamentable, perhaps depends on how a viewer wants to see life, and other humans. But in all of these painters, the naked "typical" or "average" human body or face depicted in its full ugliness, or at least its lack of complete beauty, is used to some extent as a marketing gimmick, as a way to shock and grab the viewer's -- and the art market's -- attention.

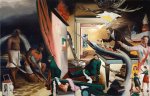

Only the New Leipzig school painters are producing figurative work that has more complex, contemporary narrative content that does not depend almost exclusively on the power of a quasi-pornographic form of nudity to shock, in order to engage viewers. The most famous member of this school, Neo Rauch, produces multi-figure hallucinatory dreamscapes whose meanings remain elusive -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neo_Rauch :

Sort of a weird cross between East Bloc Socialist Realism, Surrealism, the comic-book aesthetic of Pop Art, and the postmodern painting-collages of David Salle -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Salle and http://www.davidsallestudio.net/pindexC4.html .

But even in Neo Rauch, the content is decidedly pessimistic, dark, moody, anti-idealistic, and most definitely anti-Utopian. In China they call such work "Cynical Realism" -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cynical_realism . In Rauch the cynicism and realism are less evident, but these paintings are not exactly optimistic. These are former socialist workers going nowhere, pathetically trying to piece together a world that has fallen apart. Which is perhaps what one might expect of an artist who grew up in the DDR, and saw Marxist utopianism collapse.

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

I included a surplus of images of Bacon's work, because even though I do not like his content, at the purely "formal" level I like how his paintings look, the triptychs in particular. Francis Bacon's combination of geometry, intense color, and more organic figurative elements is very original, very beautiful, and for reasons that I do not understand, has not been taken further by contemporary figurative painters. The only thing that ruins it for me, is that once one learns the details of Bacon's biography, one realizes that in some of his paintings the figures are basically naked homosexual men fighting or bonking, or both.

It was Francis Bacon who verbally stated that he saw human bodies as "just slabs of meat", but Lucien Freud much more explicitly painted them as such, and Jenny Saville all the more so. Freud even managed to turn the Queen's head into nothing more than a shriveled egg, even though she sat patiently for her portrait for months (yes, it was commissioned, and no doubt cost a fortune.....:Wow1

At the thematic level there's more going in Frischl's paintings than the mere alla-prima representation of human corporeality, because unlike Freud's paintings, Fischl's paintings usually have multiple figures, thereby encouraging a narrative reading; even if any narrative that Fischl may have intended remains deliberately indeterminate. But like Freud, Fischl does not have much training in classical figurative drawing and painting, and to some extent he is self-taught. So Fischl's figures and portraits are never very refined, some elements are mal-proportioned, and he does not idealize, happy to convey the full realistic ugliness of the people he represents, even in portraits. For instance, Fischl's full-length portrait of his gallerist, Mary Boone, depicts the face of an old, very difficult woman who apparently is not that nice. In the painting her face is much uglier than she appears in photographs, and her face in the painting when seen first-hand is even uglier still than in reproduction. I could not find an image on-line, so I'll leave it at that.

Whether Freud and Fischl have consciously chosen "realism" as an aesthetic, or whether they paint realistic ugliness because they do not have much choice, lacking the skill to represent figures as more beautiful and refined, is an open question. Whereas Saville most definitely has the classical training, so there is a strange battle in her work between the consummate formal beauty of her technique, her mark-making and use of color, her control of tone and bravura planar painting, versus the ugliness of her content. In Saville's case anti-idealistic, anti-heroic "realism" seems much more of a choice. Whether that makes her choice brave or lamentable, perhaps depends on how a viewer wants to see life, and other humans. But in all of these painters, the naked "typical" or "average" human body or face depicted in its full ugliness, or at least its lack of complete beauty, is used to some extent as a marketing gimmick, as a way to shock and grab the viewer's -- and the art market's -- attention.

Only the New Leipzig school painters are producing figurative work that has more complex, contemporary narrative content that does not depend almost exclusively on the power of a quasi-pornographic form of nudity to shock, in order to engage viewers. The most famous member of this school, Neo Rauch, produces multi-figure hallucinatory dreamscapes whose meanings remain elusive -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neo_Rauch :

Sort of a weird cross between East Bloc Socialist Realism, Surrealism, the comic-book aesthetic of Pop Art, and the postmodern painting-collages of David Salle -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Salle and http://www.davidsallestudio.net/pindexC4.html .

But even in Neo Rauch, the content is decidedly pessimistic, dark, moody, anti-idealistic, and most definitely anti-Utopian. In China they call such work "Cynical Realism" -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cynical_realism . In Rauch the cynicism and realism are less evident, but these paintings are not exactly optimistic. These are former socialist workers going nowhere, pathetically trying to piece together a world that has fallen apart. Which is perhaps what one might expect of an artist who grew up in the DDR, and saw Marxist utopianism collapse.

********************************************

CONTINUED IN NEXT POST...

..

Last edited:

biotect

Designer

..

CONTINUED FROM PREVIOUS POST

********************************************

10. Anti-Humanism in 20th Century Figurative Painting, and its origins in 19th-century Realism

********************************************

What very few figurative artists anywhere seem able to muster today, is the psychological strength and optimism necessary to use traditional figurative skill and narrative painting as a way to express the always-present, transcendental and heroic capacities of human beings. But express these in a way that will prove convincing to people alive today; in a way that is contemporary. Human beings have never been just slabs of meat, even if Francis Bacon and most 20th century figurative painters could not see us as anything but.

To put the point another way, the problem is not that figurative art disappeared in the 20[SUP]th[/SUP] century, and was replaced by Abstraction. That’s how the problem is often put, but it’s simply not true. In a sense figuration never went away. Throughout the 20[SUP]th[/SUP] century figurative art persisted as a minority taste. Indeed, some of the more financially successful mid-20[SUP]th[/SUP] century artists have been figurative, e.g. Balthus , David Hockney , Francis Bacon , and Gerhard Richter (portraits) in his “photo-realist” paintings. As already suggested, even in the mainstream world of contemporary Art figurative painting has returned with a vengeance since the early 1980’s, when European neo-Expressionists first gained widespread acclaim: neo-Expressionists like Enzo Cucchi , Sandro Chia , and Francesco Clemente in Italy, Anselm Kiefer and Georg Baselitz in Germany, or Lucian Freud , Frank Auerbach , and R. B. Kitaj over in England – see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neo-expressionism .

So as I see it, the problem is somewhat different: figurative painting did persist in the 20[SUP]th[/SUP] century, but only as a kind of “evil twin” of its former self, as anti-humanist figurative realism for a positivistic century.

Prior to the 19[SUP]th[/SUP] century and the appearance of Goya, to describe Western European visual Art as “figurative realism” is not quite accurate, because apart from a few exceptions – e.g. Caravaggio – the content of most Western European Art was almost never realistic, but instead, was almost always thoroughly idealistic. Sure, from the Renaissance onwards, at a purely optical level, artists have aspired to ever greater degrees of representational realism -- see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Realism . And there is some truth to the modernist reading of Art history wherein the photo camera – an industrial mechanism for objective, accurate, purely optical “realistic” representation – renders obsolete the traditional aspiration towards manual representational skill. But some modernist polemics seem to suggest that representational realism was the only value that the western world's figurative tradition has held dear.